Three minutes before your presentation. Your heart is racing. Your thoughts are spiraling. Your body is in full panic mode.

You can’t control the stakes. You can’t control the outcome. But you can control your breath. And your breath, this automatic thing you do 20,000 times a day without thinking, is the remote control for your nervous system.

Four seconds in. Hold for seven. Out for eight. Repeat three times.

By the time you finish, your heart rate has slowed. The panic has downshifted. You’re still nervous (good, you’re supposed to be), but you’re no longer hijacked. This isn’t magic. It’s physiology. And it might be the most accessible tool you have for managing anxiety, anger, stress, and overwhelm.

How Your Breath Controls Your Nervous System

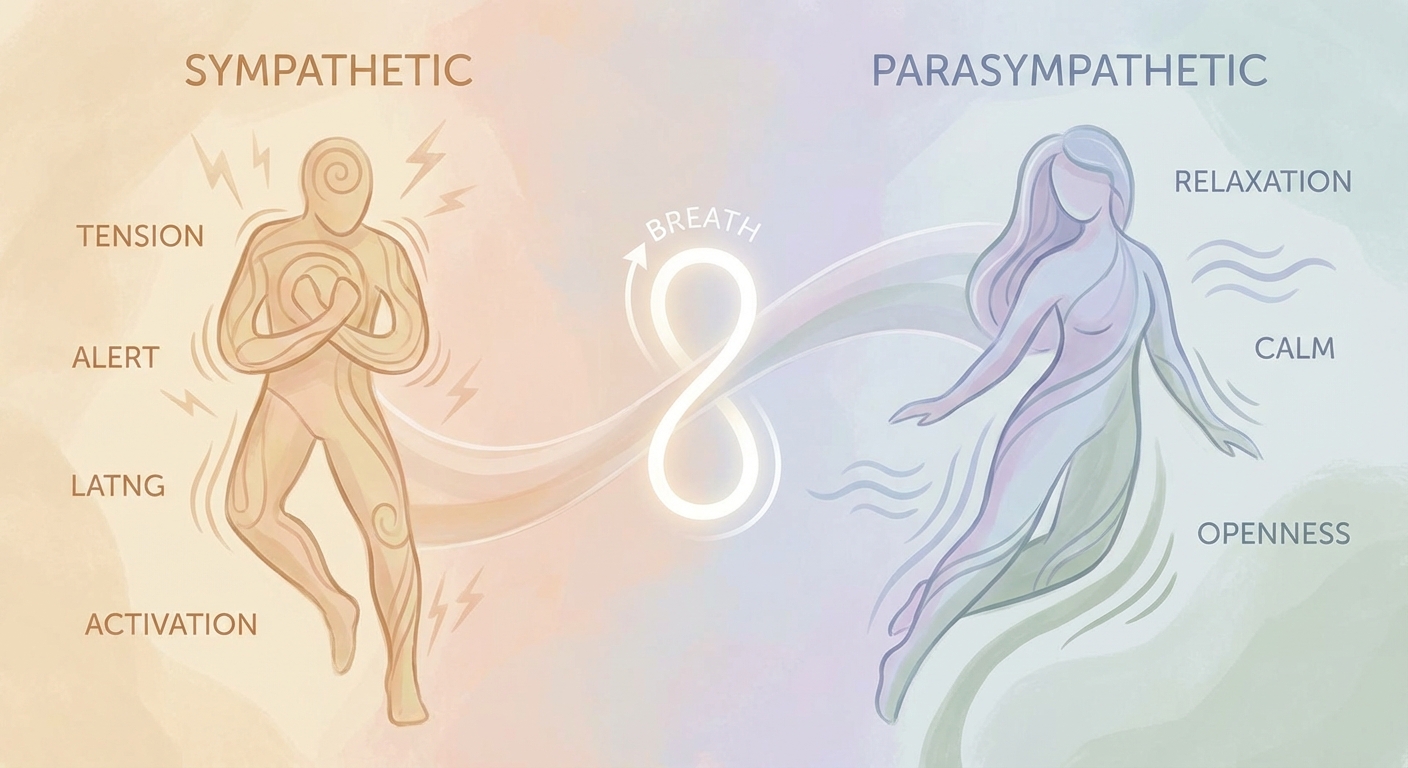

Your autonomic nervous system operates in two primary modes, and understanding this changes how you think about stress.

The sympathetic mode is your fight-or-flight response. Heart races, breath quickens, muscles tense, thinking narrows. This is survival mode, and it’s essential when you’re facing actual danger. The problem is that your body can’t distinguish between a tiger attack and an email from your boss. It responds to email stress with the same physiological cascade it would use to run from a predator. Exhausting when it’s happening daily.

The parasympathetic mode is your rest-and-digest state. Heart slows, breath deepens, muscles relax, thinking expands. This is where healing happens, where digestion works properly, where you can actually connect with other people. It’s where you want to spend most of your time, but modern life keeps pulling you into sympathetic activation.

Here’s the insight that changes everything: while you can’t directly control your heart rate or your stress hormones, you can consciously control your breath. And your body takes cues from your breathing about whether you’re safe or in danger. Fast, shallow chest breathing signals danger and activates the sympathetic system. Slow, deep belly breathing signals safety and activates the parasympathetic response.

Dr. Stephen Porges’ polyvagal theory explains the mechanism: your vagus nerve, the longest cranial nerve connecting your brain to your gut, responds to breathing patterns. Slow exhales stimulate the vagus nerve, which literally tells your body to calm down. When you breathe like you’re calm, your body believes you and becomes calm. This is why the techniques work.

Techniques That Actually Work

Not all breathwork is the same. Different patterns create different physiological effects, and the research supports specific approaches for specific needs. Understanding which technique serves which purpose helps you choose the right tool for the moment.

The 4-7-8 Breath was popularized by Dr. Andrew Weil and works particularly well for anxiety and sleep. You exhale completely through your mouth with a whooshing sound, close your mouth and inhale through your nose for 4 counts, hold for 7 counts, then exhale through your mouth for 8 counts. The specific numbers matter less than the pattern: shorter inhale, pause, extended exhale.

The long exhale is what activates your parasympathetic system. The brief hold creates a mild shift in oxygen and carbon dioxide that triggers the relaxation response. Sarah struggled with anxiety-driven insomnia for years, lying awake with her mind racing for hours. Now she does 4-7-8 breathing before bed. “By the fourth cycle, my body is calm enough to sleep. It’s not perfect every night, but it works most nights.” That consistency matters more than perfection.

Box Breathing (also called square breathing) creates a different effect. You inhale for 4 counts, hold for 4 counts, exhale for 4 counts, and hold empty for 4 counts. All sides equal, like a box. This rhythm creates balanced nervous system activation: not too sedated, not too activated. Alert calm.

Navy SEALs use this technique. If it works for people in actual life-or-death situations, it’ll work for your work presentation. Marcus practices box breathing before important meetings. “Three minutes and I’m centered. Still alert but not anxious. I can think clearly instead of reactively.” The symmetry of the pattern creates focus without drowsiness.

Coherent Breathing (also called resonance breathing) is designed for long-term nervous system training. You breathe at a rate of 5-6 breaths per minute, usually 5-second inhale and 5-second exhale, for 10-20 minutes daily. This specific rhythm synchronizes your breathing with your heart rate variability, creating optimal nervous system balance.

Research shows that regular coherent breathing practice reduces anxiety and depression symptoms, improves sleep quality, and increases stress resilience over time. The effects accumulate. Elena practices this for twenty minutes every morning. “My body knows this rhythm now. When I’m stressed during the day, I can drop into a few cycles and my whole system calms. I’ve trained the response.”

The Physiological Sigh: Your Emergency Tool

The physiological sigh is the fastest technique for real-time stress relief. Double inhale through your nose (inhale, brief pause, another quick inhale to top off your lungs), then a long, extended exhale through your mouth. Repeat 1-3 times.

Stanford neuroscientist Dr. Andrew Huberman has studied this technique extensively. The double inhale fully expands your lungs and pops open any collapsed alveoli (tiny air sacs). The extended exhale stimulates the vagus nerve, triggering immediate parasympathetic activation.

Here’s what makes this technique remarkable: it’s what you naturally do when you’re relieved. Think about the last time you received good news after worrying. You probably sighed exactly this way without thinking about it. The physiological sigh is your body’s natural reset mechanism. You can simply do it deliberately to create that relief state on demand.

Marcus uses this in traffic. “One stressful moment, one physiological sigh. Instantly better. It’s remarkable how fast it works.” Unlike techniques that require minutes of practice, the physiological sigh offers meaningful relief in seconds.

Matching Breath to Need

Different situations call for different approaches. For anxiety, the key is extending your exhale. Make it longer than your inhale: 4 counts in, 6-8 counts out. This signals safety to your nervous system. Belly breathing amplifies the effect. Put your hand on your belly and breathe deeply enough that your hand rises. This activates your diaphragm, which directly stimulates the vagus nerve. Both 4-7-8 and coherent breathing work well for persistent anxiety.

For anger, the goal is interrupting the spiral before it peaks. Count your breath with simple rhythm: in for 4, out for 4. The counting gives your mind something to focus on besides the anger trigger. Brief holds between inhale and exhale create a slight pause that allows your rational brain to come back online. Anger hijacks your prefrontal cortex; breath gives you a moment to reclaim it.

For sleep, 4-7-8 breathing was specifically designed for this purpose. You can also try a body scan with breath: breathe into each body part sequentially from feet to head, releasing tension as you exhale. Extended exhales (4 counts in, 8 counts out) help tip your nervous system toward rest. If you’re interested in broader approaches to rest and recovery, our piece on the art of doing nothing explores why genuine rest is so essential.

For focus, box breathing creates the alert, balanced state you need for cognitive work. Even just three deep breaths before starting a task helps you center before beginning. If you struggle with managing your energy throughout the day, breathwork transitions can mark shifts between activities.

Breathwork Is Different From Meditation

People often conflate these practices, but they serve distinct purposes. Meditation is primarily an awareness practice. You notice thoughts, sensations, and breath. You return attention to your object of focus when your mind wanders. The goal is training attention and building present-moment awareness.

Breathwork is physiological intervention. You actively manipulate your breath pattern to create specific nervous system effects. You’re not just noticing your breath; you’re deliberately changing it to change your state.

You can do both, and they complement each other well. Meditation builds awareness over time. Breathwork regulates your state in the moment. Many people find breathwork more accessible because it’s more active and the effects are more immediate.

Sarah told us: “I can’t meditate. My mind won’t quiet. But breathwork? That I can do. I’m doing something, which my brain accepts. And it works faster than meditation for me.” If traditional meditation hasn’t worked for you, breathwork offers a more active path to similar benefits. For those who want to explore meditation alongside breathwork, our beginner’s guide to meditation offers accessible starting points.

Building Your Breath Practice

You don’t need a special space, special equipment, or significant time investment. You need your lungs and a few minutes of intention.

The key to making breathwork habitual is linking it to transitions you already have. Morning breath means taking five cycles of your chosen technique before getting out of bed. This sets your nervous system tone for the day. Transition breath happens between activities: arriving at work, before starting a meeting, after finishing a difficult task. These mark shifts and prevent stress from carrying over. Stress breath is intervention in the moment. When you notice stress, anxiety, or anger rising, intervene with breath before you’re fully hijacked. Evening breath becomes part of your wind-down routine, signaling to your body that it’s time to shift toward rest.

Apps can help initially. Breathwrk, Breath Ball, and Oak guide you through patterns until they become automatic. But the beauty of breathwork is that you’ll eventually need nothing but yourself. Marcus set three daily reminders initially: morning, lunch, evening, just three minutes each time. “After a month, I didn’t need reminders. My body craved the practice.”

The Immediate Access Advantage

This is what makes breathwork uniquely powerful: it’s always available.

Anxiety at work? You can’t exactly start a meditation session at your desk, but you can absolutely do three cycles of 4-7-8 breathing without anyone noticing. Anger in traffic? You can’t change the situation, but you can change your physiological response. Can’t sleep? A sleeping pill takes time to work and has side effects. Breathwork is instant and has no side effects. No app required. No equipment. No special space. Just you and your lungs.

Elena travels constantly for work. “I can’t bring my meditation cushion or my morning routine. But I can always breathe. Flight anxiety? Breathwork. Jet lag? Breathwork. Pre-meeting nerves? Breathwork. It’s my most portable tool.”

Start Right Now

Not tomorrow. Not when you’re less busy. Now.

Wherever you are, try this: Inhale for 4 counts. Hold for 4. Exhale for 4. Hold for 4. Repeat three times.

Notice what shifts. Your heart rate. Your muscle tension. Your mental clarity. Something changed, didn’t it? That shift is available to you anytime you choose to access it.

This week, pick one breathwork technique. Practice it three times daily: morning, midday, evening. Just three minutes each time. Notice what changes in your stress response, your sleep, and your ability to regulate your emotions instead of being swept away by them.

You’re three minutes from a calmer nervous system. All you have to do is breathe deliberately.

This article draws on research from Dr. Andrew Weil (4-7-8 breathing), Dr. Stephen Porges (polyvagal theory), Dr. Andrew Huberman (physiological sigh research), James Nestor (Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art), and the growing body of clinical research on breathwork for mental health.

Sources: Dr. Andrew Weil’s breathwork research, Dr. Stephen Porges’ polyvagal theory, Dr. Andrew Huberman’s neuroscience research at Stanford, James Nestor’s “Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art.”.