You got the promotion. You’re in the meeting with senior leaders. People are asking for your expertise on topics you’ve spent years developing. And the voice in your head is screaming: “They’re going to figure out you don’t know what you’re doing.” Your resume is impressive. You’ve succeeded at every level so far. Colleagues seek your input and trust your judgment. You’re objectively qualified for this role. But you feel like a fraud who’s somehow fooled everyone, always one tough question away from being exposed as incompetent.

Welcome to impostor syndrome. The persistent belief that your success is due to luck, timing, or tricking people rather than actual competence. The fear that you’ll be “found out” and revealed as the fraud you believe yourself to be. If this sounds familiar, you’re in remarkably good company. Research from Pauline Clance and Suzanne Imes, who first identified the phenomenon in 1978, shows that approximately 70% of people experience impostor syndrome at some point in their careers. High achievers experience it more intensely than average performers. And it affects performance, job satisfaction, and career advancement in measurable ways. The good news is that impostor syndrome, despite feeling like truth, is a cognitive distortion. And you can learn to work through it without it destroying your career or your mental health.

Why High Performers Experience It Most

Logic would suggest that confident, successful people wouldn’t feel like impostors. But research consistently shows the opposite. The more you achieve, the more likely you are to experience impostor feelings. Understanding why can help you recognize these feelings for what they are.

The impostor paradox operates through a cruel mechanism. The more you achieve, the more opportunities you receive for things you haven’t done before. Each new level of success brings new challenges that exceed your previous experience. Your competence got you here, but “here” is beyond what you’ve done before, so you feel incompetent despite being the most competent person available for the role. Accomplished people also tend to have high standards. You compare your internal experience, the doubts, struggles, and mistakes you see, to others’ external presentation, the confidence and polish they display. This creates a constant sense of falling short because you’re comparing your behind-the-scenes footage to everyone else’s highlight reel.

Dr. Valerie Young, who has studied impostor syndrome for decades, notes that the people who don’t experience impostor syndrome typically fall into one of two categories: either they haven’t pushed beyond their comfort zone, so they never face the uncertainty that triggers these feelings, or they lack the self-awareness to recognize their limitations. Neither is actually better than experiencing impostor syndrome while growing. The feeling isn’t evidence that you don’t belong. It’s evidence that you’re stretching into new territory. That’s called growth.

The Competence-Confidence Gap

There’s a period in skill development where your actual competence outpaces your felt sense of competence. You’re capable, but you don’t feel capable yet. Understanding this gap can help you trust yourself even when your feelings suggest otherwise.

The learning curve moves through predictable stages. In the first stage, unconscious incompetence, you don’t know what you don’t know. This often produces false confidence because you can’t see your own limitations. In the second stage, conscious incompetence, you become aware of how much you don’t know, and your confidence crashes. This is the “valley of despair” in learning curves. The third stage, conscious competence, is where impostor syndrome peaks. You’re developing real skill, but it still requires effort and focus. You can do the job, but it doesn’t feel natural or automatic yet. Because it requires effort, you conclude you must be faking it. Finally, in the fourth stage, unconscious competence, skill becomes automatic and confidence catches up to ability.

Most people experiencing impostor syndrome are somewhere in that third stage. They’re actually competent, but competence still requires conscious effort, so they interpret that effort as evidence of fraudulence. The truth is simpler: everyone feels like they’re faking it when they’re learning. That’s not being a fraud. That’s being in transition between levels of mastery. The effort you feel isn’t evidence of inadequacy. It’s evidence that you’re doing something hard while you’re still getting good at it.

Recognize Your Specific Triggers

Certain workplace situations intensify impostor feelings. Recognizing your personal triggers helps you prepare for them rather than being blindsided.

Starting a new role or receiving a promotion is a classic trigger. You haven’t proven yourself at this level yet, so every task feels like a test of whether you actually belong. Being the “only” in a room, whether the only woman on an engineering team, the only person of color in leadership, or the only young person among experienced colleagues, amplifies impostor feelings because your differences feel like disadvantages. High-visibility projects where stakes are high and many people are watching create pressure, because failure would be public rather than private.

Perhaps counterintuitively, receiving praise can trigger impostor feelings. Compliments feel undeserved, and you assume the person complimenting you either doesn’t see the full picture or is just being polite. Comparing yourself to colleagues who seem confident and capable while you see your own doubts reinforces the belief that you’re uniquely inadequate. Notice that none of these situations involve actual incompetence. They’re situations where you feel exposed, and your internal critic uses that vulnerability to attack. The feeling of being a fraud and actually being a fraud are very different things.

Build Your Evidence File

Impostor syndrome survives by systematically discounting your actual competence. The antidote is evidence you can’t discount, documented and specific.

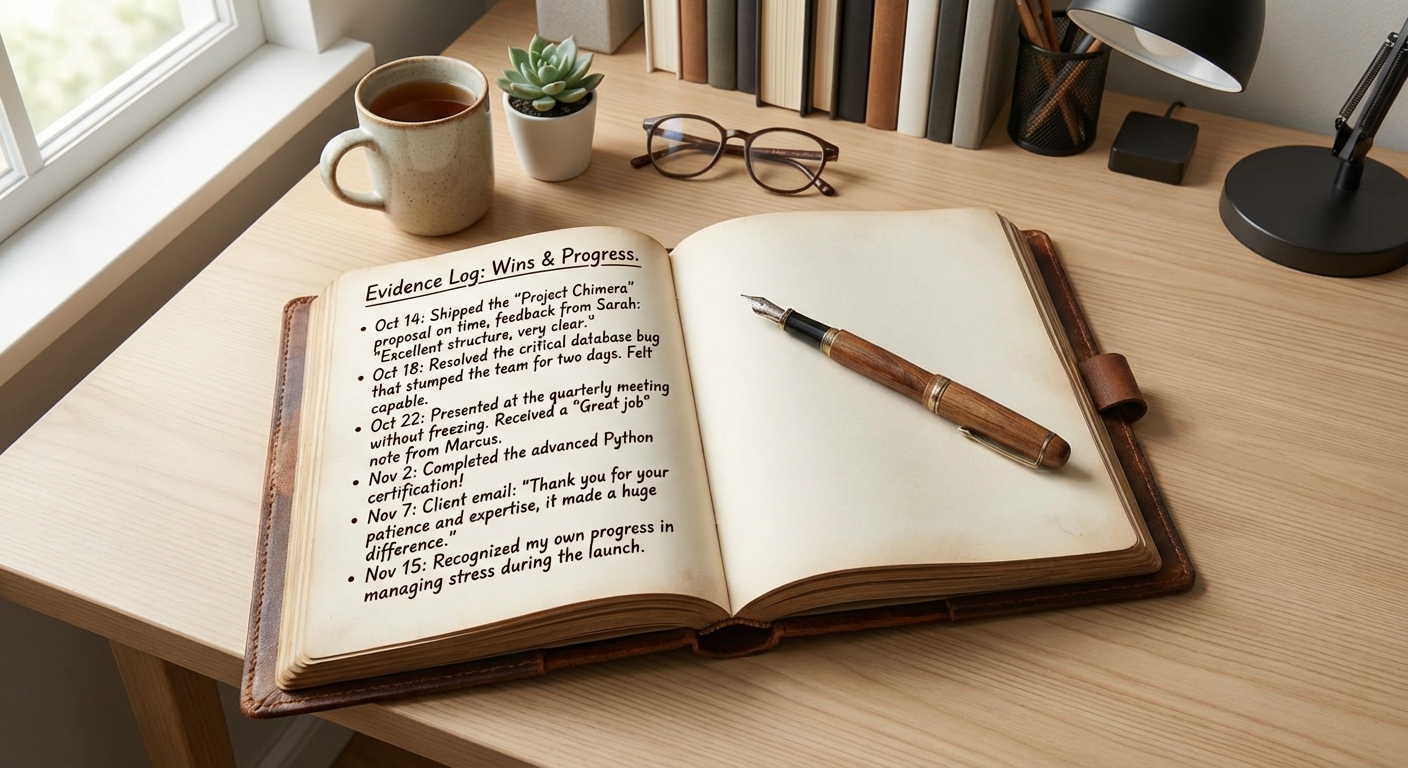

Start an accomplishment log and update it regularly. Record every positive outcome, every problem you solved, every piece of positive feedback, every completed project, and every skill you demonstrated. Write it down with specifics. Not “did okay on presentation,” but “delivered presentation to 50 stakeholders, received positive feedback from three VPs, presentation led to project approval.” When impostor feelings arise, review your log. You have documented evidence of competence. The feeling that you’re a fraud doesn’t match the facts.

Track additional indicators of your value. Note times people sought your expertise, because they trust your knowledge enough to ask. Record decisions you made that proved correct, demonstrating your judgment works. Document problems only you could solve, showing your skills are unique and valuable. Over time, evidence accumulates. The impostor narrative becomes harder to maintain when confronted with months or years of proof that you’re actually competent.

Cognitive behavioral therapy research suggests that challenging distorted thoughts with evidence is one of the most effective ways to change thinking patterns. You’re not trying to become delusionally confident. You’re trying to see yourself accurately rather than through the distorted lens of impostor syndrome. When the internal voice says “you’re a fraud,” you can point to your evidence file and respond with documented facts.

Reframe the Impostor Narrative

Impostor syndrome involves specific thought patterns that you can learn to challenge. The thoughts feel like truth, but they’re interpretations, and interpretations can be questioned.

When you think “I only got this because I was lucky,” try reframing: “Luck might have played a role, but I was prepared when opportunity came. And I’ve performed well since getting here. That’s not all luck.” When you think “Everyone else knows more than me,” consider: “Everyone knows different things. I have expertise they don’t have. And everyone feels like they don’t know enough sometimes.” When you think “They’re going to realize I don’t belong here,” challenge that with: “They hired me because I’m qualified. I’ve delivered results. If they thought I didn’t belong, there’s been plenty of opportunity for them to notice.”

When you think “I haven’t earned this success,” remember: “I’ve worked for this. I’ve developed skills. I’ve overcome challenges. This isn’t charity; this is the result of effort.” The goal isn’t to become arrogant or to ignore genuine areas for growth. The goal is to see yourself accurately, to give yourself credit for what you’ve actually accomplished rather than explaining it all away as luck or deception.

Work Effectively Despite the Feeling

You probably won’t eliminate impostor syndrome completely. But you can learn to work effectively despite it, which is ultimately what matters.

The first step is recognizing the feeling when it arises without merging with it. “Oh, impostor syndrome is here again.” Naming it creates distance between you and the thought. It transforms “I am a fraud” into “I’m having the thought that I’m a fraud,” which is very different. Acknowledge the feeling without letting it control your behavior. “I feel like a fraud, but I’m going to do this anyway.” Feelings are data, not directives. You can feel uncertain and still act competently.

Act despite the feeling. Speak in the meeting even though you feel unqualified. Submit the proposal even though you feel it’s not good enough. Take the risk even though you fear exposure. Then review the evidence afterward. “I was terrified, but I did it and it went fine. The feeling lied to me.” Over time, you build a track record of feeling like an impostor but performing well anyway. The feelings may persist, but they lose their power to control your behavior. You develop a new relationship with self-doubt, one where it exists but doesn’t run the show.

Find Support and Normalize the Experience

One powerful way to reduce impostor feelings is realizing that almost everyone experiences them. The person who seems unshakably confident? They probably feel like a fraud sometimes too.

Talk to colleagues you respect about feeling like an impostor. Most will admit they feel it too. When you discover that the person you think is brilliant and confident also struggles with self-doubt, it normalizes the experience. It’s not that you’re uniquely inadequate; it’s that this is a normal response to challenge and growth. Some workplaces are beginning to create spaces for these conversations: impostor syndrome support groups, mentorship programs that address it directly, leaders sharing their own experiences publicly. When the culture acknowledges that impostor feelings are normal rather than shameful, they lose power.

Mentorship helps significantly. Having someone more experienced validate your abilities and normalize struggle provides external perspective when your internal view is distorted. Peer support matters too, connecting with others at similar career stages who experience similar feelings. Therapy, particularly cognitive behavioral approaches, can address underlying thought patterns for people who find impostor syndrome significantly affecting their quality of life. And regular, specific feedback about what you’re doing well grounds you in reality rather than leaving you to guess.

Your Invitation

If you’re experiencing impostor syndrome at work right now, know this: you’re not alone, and you’re not actually a fraud. The feeling is a normal response to growth and challenge. It means you’re pushing yourself into new territory. That takes courage even when it doesn’t feel courageous.

Start collecting evidence of your actual competence. Write down your wins, your solved problems, your positive feedback. Build a file you can return to when doubt gets loud. Talk to someone you trust about feeling this way. Breaking the silence reduces shame and often reveals that the person you’re talking to feels it too. Keep doing the work despite the feeling. Your growth is real, your competence is developing, and the work you’re doing matters.

The fraud would have been exposed by now. The fact that you’re still here, still advancing, still being asked for your contribution, is evidence. Trust that evidence over the feeling. You belong here. You earned this. You’re capable. And the doubt you feel? That’s just your brain processing growth. Let it be there. Do the work anyway.

For more on building genuine confidence from the inside out, explore build unshakeable confidence. If you’re considering a significant career change and self-doubt is holding you back, career pivot at 40+ addresses the unique challenges of major transitions. And for deeper work on transforming your relationship with your inner critic, inner critic as friend offers a different perspective on that voice that tells you you’re not enough.

Sources: Pauline Clance and Suzanne Imes impostor phenomenon research, Dr. Valerie Young’s work on impostor syndrome, cognitive behavioral therapy principles.