Everyone talks about resilience like it’s a muscle you can strengthen through sheer force of will. Just push through. Develop grit. Bounce back faster. The implication is that if you’re struggling, you simply haven’t worked hard enough at being tough.

But a striking finding from recent research tells a different story. When scientists studied what actually predicts psychological resilience, they discovered that meaningful work explains 40 percent of resilience’s protective effects on mental health. Not positive thinking. Not stress management techniques. Not even social support, though that matters too. Meaning. The sense that what you do actually matters.

This finding doesn’t just challenge popular assumptions about resilience. It reframes the entire conversation about sustainable wellbeing at work. If nearly half of resilience’s benefits flow through meaning, then building resilience isn’t primarily about becoming tougher. It’s about connecting more deeply to purpose.

What the Research Actually Shows

The study, published in the journal Behavioral Sciences, examined 197 emergency medicine professionals following the COVID-19 Omicron surge. These were people who had endured one of the most psychologically demanding periods in modern healthcare. The researchers wanted to understand why some clinicians maintained their mental health while others experienced significant strain.

The findings were clear: higher perceived resilience significantly predicted lower mental health strain. That much was expected. But the surprising discovery was the mechanism. When researchers analyzed the pathway between resilience and mental health outcomes, they found that meaningful work accounted for 40 percent of the relationship. Resilience didn’t just help people endure difficulty. It helped them find meaning in their work, and that meaning was what actually protected their mental health.

Dr. Eric Nestler, a leading researcher on stress and resilience, notes that this aligns with broader findings in the field. “It is possible to develop treatments that promote mechanisms of natural resilience in individuals who are inherently more susceptible,” he explains. But this study suggests something more accessible: you can cultivate resilience not just through clinical intervention, but through the daily experience of meaningful engagement with your work.

The implications extend far beyond healthcare. If meaning mediates resilience this powerfully in high-stress environments, it likely plays a similar role in every workplace. The employee who can’t articulate why their work matters isn’t just uninspired. They may be structurally more vulnerable to burnout, anxiety, and the accumulated toll of chronic stress.

The Meaning-Resilience Loop

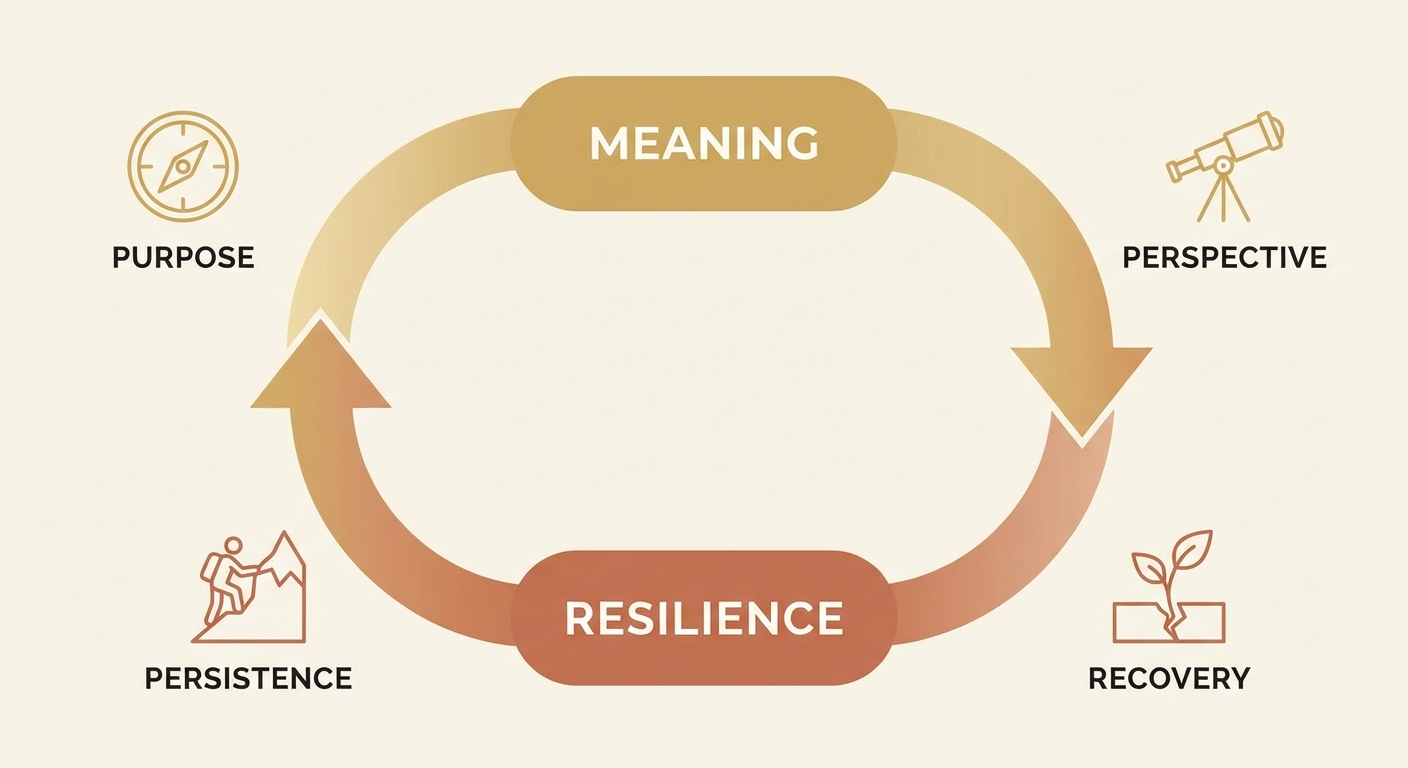

Understanding how meaning and resilience interact requires looking at the relationship from both directions. It’s not simply that meaningful work makes you more resilient. It’s that resilience also helps you find and sustain meaning. The relationship is circular, a feedback loop that can spiral upward or downward depending on the conditions.

When work feels meaningful, you’re more likely to persist through difficulties. Challenges become opportunities for growth rather than just obstacles to endure. Setbacks feel temporary rather than defining. The meaning you’ve attached to your work provides a reason to push through moments that would otherwise feel pointless or overwhelming.

But the loop works in reverse too. Resilience, the capacity to adapt and recover from adversity, helps you maintain perspective when meaning temporarily fades. Every job has mundane tasks, frustrating colleagues, and periods when purpose feels distant. Resilient people can weather these stretches without abandoning the larger narrative of meaning that sustains their engagement.

The 2025 Mental Health at Work Report from Mind Share Partners confirms that this loop has measurable organizational consequences. Employees who work at companies that support their mental health are twice as likely to report no burnout or depression. But support isn’t just about wellness programs or mental health days. It’s about creating conditions where meaningful work is possible, where employees can connect their daily tasks to outcomes they genuinely care about.

Finding Meaning in Imperfect Circumstances

The research raises an uncomfortable question: what if your current work doesn’t feel meaningful? Not everyone has the luxury of a purpose-driven job. Not everyone can quit and pursue their passion. For most people, the challenge isn’t finding meaningful work from scratch. It’s finding meaning within the constraints of their current situation.

Self-Determination Theory, developed by psychologists Edward Deci and Richard Ryan, offers a framework for understanding how meaning emerges even in imperfect circumstances. The theory identifies three core psychological needs: autonomy (the sense that you have choice and control), competence (the feeling that you’re effective at what you do), and relatedness (connection with others). When these needs are met, people experience their work as more meaningful, regardless of the job title or industry.

This suggests that meaning isn’t something you find fully formed in the perfect job. It’s something you construct through how you engage with your work. A customer service representative who focuses on genuinely helping each caller experiences more meaning than one who just processes tickets. A manager who invests in developing their team members experiences more meaning than one who simply assigns tasks. The job is the same. The meaning is not.

Research from the Greater Good Science Center at UC Berkeley supports this construction view of meaning. Their studies show that meaning emerges from contribution, from the sense that your efforts benefit others or advance something larger than yourself. You don’t need a job that’s designed to be meaningful. You need to actively identify how your work contributes, even in small ways, to outcomes you value.

The Organizational Responsibility

While individuals can cultivate meaning, the research also points to organizational responsibility. Companies can’t simply expect employees to manufacture meaning out of nothing. The conditions have to allow for it. This means more than mission statements and values posters. It means structural decisions about how work is designed, distributed, and recognized.

The 2025 workplace trends data reveals that organizations prioritizing psychological safety and meaningful engagement see measurable returns: lower turnover, reduced burnout, higher productivity. But many organizations still treat meaning as a nice-to-have rather than a strategic necessity. They focus on efficiency and output while neglecting the psychological infrastructure that makes sustainable performance possible.

A skills-based approach to mental health, as recommended by the Society for Human Resource Management, treats meaning-making as a developable capacity. Rather than waiting for employees to burn out and then offering intervention, organizations can proactively teach the skills of meaning construction: how to identify contribution, how to reframe challenges, how to connect daily tasks to larger purpose. These aren’t soft skills in the dismissive sense. They’re the skills that make the difference between surviving work and thriving through it.

For individuals, this means being strategic about the conversations you’re avoiding with your manager or organization. If your work feels meaningless, that’s information worth sharing. It might lead to restructuring responsibilities, connecting to different projects, or simply understanding better how your role contributes to outcomes you hadn’t considered. Organizations can’t address meaning deficits they don’t know exist.

Building Your Meaning Practice

Understanding the meaning-resilience connection is step one. Translating it into practice is where the real work begins. The research suggests several evidence-based approaches that strengthen both sides of the loop simultaneously.

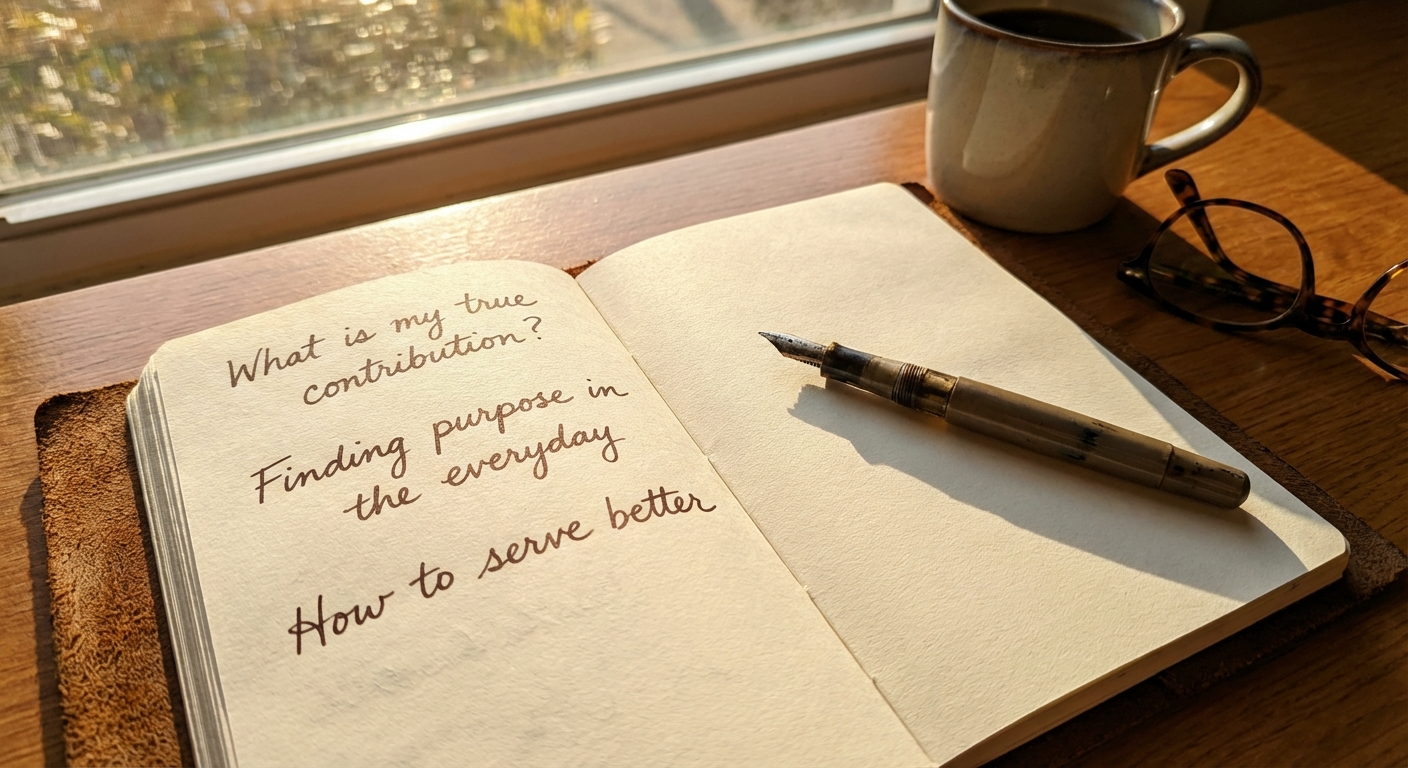

First, articulate your contribution explicitly. Many people perform meaningful work without recognizing its meaning because they’ve never verbalized it. Write down who benefits from what you do and how. Be specific. “I help people” is vague. “I help parents feel confident that their children will get to school safely” (a school bus driver) or “I help anxious families understand complex financial decisions” (a financial advisor) connects daily tasks to human outcomes.

Second, seek feedback that connects effort to impact. One reason meaning erodes is that we rarely see the downstream effects of our work. Actively seek out stories of impact, whether from clients, colleagues, or data. When you hear about the difference your work made, the meaning loop strengthens.

Third, invest in workplace relationships. The relatedness component of Self-Determination Theory isn’t just about feeling liked. It’s about experiencing your work as embedded in a web of mutual support and shared purpose. When you know others who care about the same outcomes you do, meaning feels less fragile and more sustainable.

Finally, distinguish between meaning and pleasure. Not every task will feel enjoyable, and that’s fine. Meaning often involves difficulty, the hard conversation, the challenging project, the extra effort that makes a real difference. Research shows that meaning and happiness aren’t the same thing, and pursuing one doesn’t guarantee the other. But meaning provides something happiness can’t: a reason to persist when things get hard.

Your Invitation

The 40 percent finding isn’t just a research statistic. It’s an invitation to rethink what resilience actually requires. If nearly half of resilience’s protective effects flow through meaningful work, then building resilience isn’t primarily about becoming tougher, more disciplined, or better at stress management. It’s about connecting more deeply to purpose in your daily work.

This doesn’t mean your job needs to save the world. It means you need to know, in concrete terms, how your work contributes to outcomes you value. That knowledge isn’t automatic. It requires deliberate construction and regular renewal.

The research is clear: resilience matters, and its benefits are at least partly a function of meaningful work. The organizations that understand this will build cultures where meaning is possible. The individuals who understand it will take responsibility for finding work they can love, not by chasing perfect jobs, but by actively constructing meaning in the work they have.

That construction project begins with a simple question: Who benefits from what I do, and why does that matter to me?

The answer might be the most important thing you write this year.

Sources: Perceived Resilience, Meaningful Work, and Mental Health (Behavioral Sciences 2025), Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan), 2025 Mental Health at Work Report, SHRM Workplace Mental Health, ScienceDaily, Greater Good Science Center.