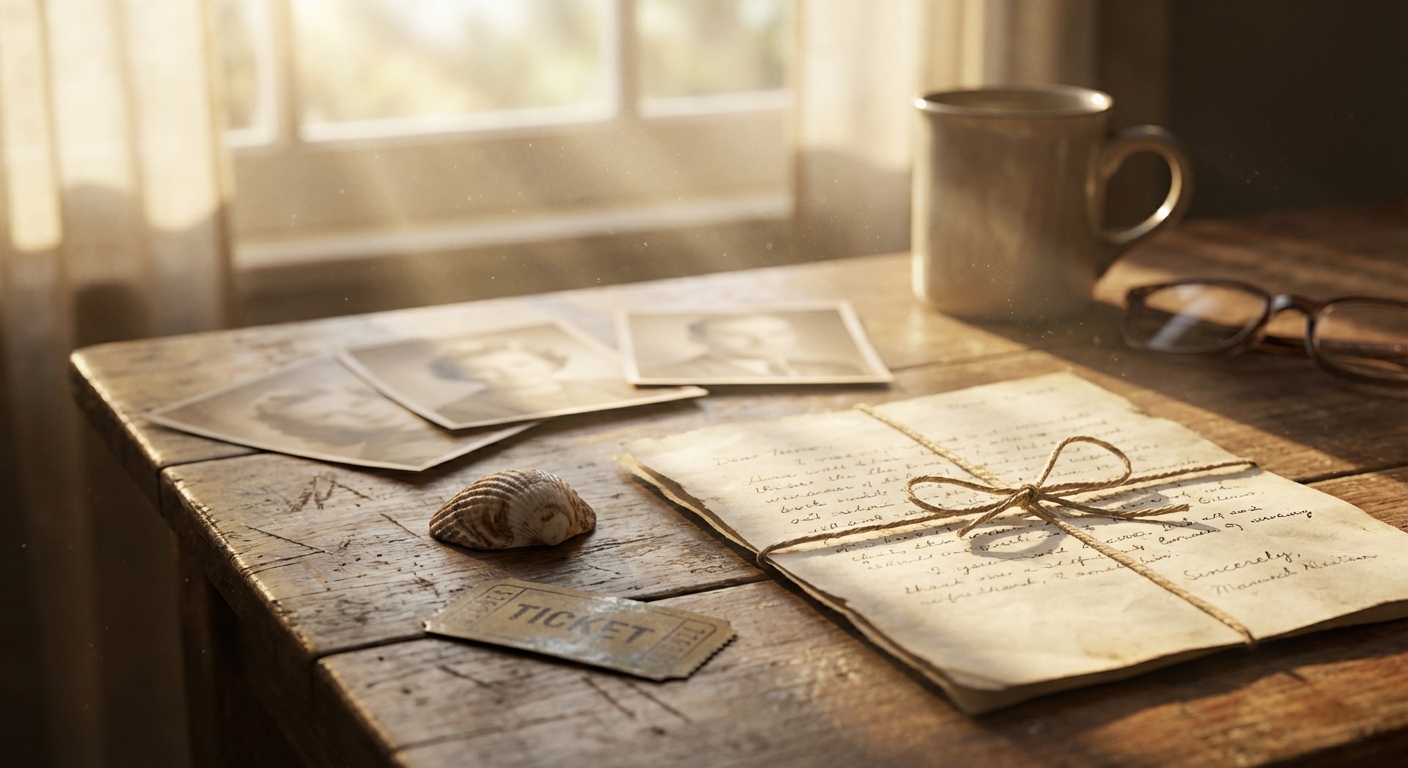

The song comes on unexpectedly, something from a decade ago, and suddenly you’re somewhere else. You’re in that apartment with those friends, living that version of your life that feels both impossibly distant and startlingly close. There’s a sweetness to the feeling, but also an ache. You’re happy remembering, and also sad that the memory is all you have. This is nostalgia: that bittersweet longing for a past you can’t return to.

For most of history, nostalgia was considered a problem. The term was coined in 1688 by a Swiss physician describing a mysterious illness affecting soldiers who longed for home. For centuries afterward, it was classified as a medical condition, a kind of psychological weakness that needed to be cured. People who dwelt too much on the past were thought to be avoiding the present, stuck in what was instead of engaging with what is.

Modern research tells a very different story. Over the past two decades, psychologists have systematically studied nostalgia and found something surprising: this supposedly problematic emotion is actually a psychological resource. When you feel nostalgic, you’re not just indulging in sentiment. You’re accessing a tool that can improve your mood, strengthen your sense of self, and connect you more deeply to the people and experiences that matter.

What Research Actually Shows

The scientific rehabilitation of nostalgia began at the University of Southampton, where psychologists Constantine Sedikides and Tim Wildschut started examining its effects systematically. Their research and subsequent studies have demonstrated that nostalgic experiences reliably increase several markers of psychological wellbeing, including meaning in life, optimism, self-esteem, social connectedness, and positive affect.

A 2024 study published in Social Psychological and Personality Science identified one of the key mechanisms. Researchers Naidu, Gabriel, Wildschut, and Sedikides found that nostalgia increases psychological wellbeing partly through what they call “collective effervescence,” a potent sense of connection to others and a feeling of transcendence. When you remember that birthday party, that road trip, that season of your life when everything seemed possible, you’re not just recalling events. You’re reconnecting with the web of relationships that gave those events meaning.

The emotional signature of nostalgia is distinctive. Unlike purely positive emotions, nostalgia is bittersweet, containing both warmth and longing, happiness and sadness. Researchers at the Greater Good Science Center note that this complexity is part of what makes nostalgia psychologically valuable. It’s not escapism or denial. It’s a nuanced engagement with your own history that acknowledges both what was beautiful and what is lost.

The benefits extend beyond mood improvement. Research published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology found that nostalgia increases psychological wellbeing partly by enhancing feelings of authenticity, the sense of being aligned with your true self. When you remember experiences that felt meaningful, you’re reminded of who you really are beneath the roles and obligations of daily life. The memory becomes a touchstone for identity.

Nostalgia as a Psychological Resource

One of the most intriguing findings is that nostalgia appears when we need it most. Research during the COVID-19 pandemic found that nostalgic experiences helped repair negative moods by boosting positive emotions about both the present and future. People who engaged with nostalgic memories reported stronger psychological resilience during uncertain times. The past wasn’t an escape from the difficult present; it was a resource for navigating it.

This pattern appears across contexts. When people feel lonely, nostalgia counteracts the feeling by activating memories of social connection. When people face existential threats or feel uncertain about meaning, nostalgia provides continuity and significance. When self-esteem is threatened, nostalgic memories remind people of their worth and the relationships that validate it. The emotion seems designed to address specific psychological needs, arising when those needs are most acute.

The University of Florida’s coverage of nostalgia research describes it as a kind of psychological immune system. Just as physical immunity responds to threats with targeted defenses, nostalgia responds to emotional challenges with targeted psychological resources. Feeling disconnected? Here are memories of belonging. Feeling lost? Here’s a reminder of who you’ve been and what matters to you. Feeling hopeless about the future? Here’s evidence that good things have happened before and can happen again.

This doesn’t mean nostalgia is always helpful. Some research suggests that people with strong worry habits may experience enhanced anxiety after nostalgic experiences, possibly because the contrast between a idealized past and uncertain present becomes painful rather than comforting. Like any psychological tool, nostalgia works best when engaged skillfully.

The Types of Nostalgia That Help

Not all nostalgic experiences are equally beneficial. Researchers distinguish between different forms of nostalgia, and the distinction matters for understanding how to engage the emotion productively.

Personal nostalgia, focused on your own past experiences, tends to produce the clearest wellbeing benefits. These are the memories of experiences you lived: the summer job, the first apartment, the friendship that shaped you. Personal nostalgia increases meaning and connectedness by reminding you that your life has contained genuine significance.

Anticipatory nostalgia, the bittersweet awareness that a current experience will someday be a memory, is more complex. While it can enhance present-moment awareness and appreciation, it can also interfere with full engagement by introducing awareness of future loss into present experience. The trick is noticing when anticipatory nostalgia enriches the present versus when it distracts from it.

Social nostalgia, missing shared experiences with others rather than solitary memories, shows particularly strong effects on connectedness. The memories that matter most often involve other people, and remembering together amplifies the benefits. This is one reason why family gatherings, high school reunions, and looking through old photos with friends can feel so meaningful.

How to Engage Nostalgia Skillfully

Given the research on nostalgia’s benefits, how do you engage it intentionally and productively? Several principles emerge from the literature.

Make it relational. The most beneficial nostalgic experiences tend to involve memories of connection, times when you felt close to others, part of something larger than yourself. When you deliberately call up nostalgic memories, focus on who was there, not just what happened. The people in your memories are often the source of the emotion’s psychological power.

Let the bittersweet be bittersweet. Nostalgia’s complexity is part of its value. Don’t try to eliminate the longing, the awareness that the memory is a memory rather than present reality. That ache is what distinguishes nostalgia from simple pleasant recall and may be connected to its psychological benefits. The sweetness and sadness together create something richer than either alone.

Use it, don’t live there. Nostalgia works best as a resource you draw on, not a place you reside. The goal isn’t to replace present experience with past memory but to let past memory inform and enrich present experience. After a nostalgic moment, return to the present with whatever the memory gave you: a sense of meaning, a feeling of connection, a reminder of what matters.

Share it when possible. Looking at photos together, telling stories from the past, sharing memories with people who were there, these social forms of nostalgia tend to amplify the benefits. You’re not just remembering; you’re reconnecting. The memory becomes a bridge between your past self and present relationships.

Trust its timing. If nostalgic feelings arise spontaneously, they may be addressing a need you haven’t consciously recognized. Loneliness, meaninglessness, and disconnection can operate below awareness, and nostalgia may be your psyche’s attempt to respond. Instead of dismissing the feeling as unproductive dwelling, consider what it might be offering.

New Year’s Eve and the Nostalgic Turn

Tonight, as one year becomes another, nostalgia is almost inevitable. The changing calendar invites reflection on what was, and that reflection naturally takes us to memories of people, places, and experiences that shaped the year now ending. For many people, this nostalgic turn feels indulgent or unproductive, something to push past on the way to forward-looking resolutions.

The research suggests otherwise. Engaging your nostalgia tonight isn’t avoiding the future; it’s preparing for it. The memories that surface when you let them, the people you find yourself missing, the experiences that feel most alive when you recall them, are data about what matters to you. They’re evidence of meaning, proof that your life has contained things worth missing.

Let yourself feel it. The song that brings you somewhere else, the photo that catches your breath, the name that surfaces unbidden, these aren’t distractions from the work of new-year planning. They’re insights into what you actually value, delivered in the form your psyche naturally prefers.

Your Invitation

Tonight or tomorrow, try a deliberate nostalgic practice. Choose a memory from the closing year that felt meaningful, a moment when you felt connected, present, or fully yourself. Close your eyes and inhabit it. Who was there? What did it feel like in your body? What made it matter?

Notice the emotion that arises, probably bittersweet, happy and sad at once. Don’t try to resolve the complexity. Let the memory be what it is: evidence that your life contains, and has contained, real meaning. Something that was worth living, and remains worth remembering.

Then return to the present moment with whatever the memory gave you. Maybe it’s gratitude for the people who’ve shaped your year. Maybe it’s clarity about what you want more of in the year ahead. Maybe it’s simply a reminder that life, with all its difficulties, has also held genuine beauty.

Nostalgia isn’t dwelling in the past. It’s consulting the past, drawing on its resources, letting it inform your present and future. The research is clear: this supposedly problematic emotion is actually a gift. Tonight seems like a good night to unwrap it.

Sources:

- Nostalgia: A potential pathway to greater well-being, ScienceDirect

- Nostalgia Increases Psychological Wellbeing Through Collective Effervescence, SPPS 2024

- Nostalgia confers psychological wellbeing by increasing authenticity, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology

- Five Ways Nostalgia Can Improve Your Well-Being, Greater Good Science Center

- The Psychology of Nostalgia, University of Florida

- Nostalgia moderates mood and optimism during COVID-19, PubMed

- Nostalgia and Well-Being in Daily Life, PMC