The alarm goes off. You rush through breakfast or skip it entirely. Speed-walk to your car. Battle traffic while mentally rehearsing the day’s demands. Gulp coffee at your desk between emails. Sprint through back-to-back meetings. Scarf down lunch without tasting it. Power through the afternoon on caffeine and momentum. Commute home exhausted. Microwave something. Zone out on your phone. Collapse into bed. Repeat. This is modern life for millions of people, and we wonder why we’re burned out, disconnected, and constantly feeling like there’s never enough time, never enough space, never enough us to go around.

There’s another way. It’s not about doing less, though that sometimes helps. It’s about doing differently. It’s called slow living, and it might be the antidote to our culture’s addiction to speed. Carl Honoré, who wrote “In Praise of Slowness” and has become one of the movement’s most articulate advocates, describes slow living not as doing everything at a snail’s pace but as doing everything at the right speed, the speed that allows for quality, connection, and presence. It’s a rebellion against the assumption that faster is always better, that efficiency should trump experience, that busy equals important. What if we stopped rushing through life and actually experienced it?

What Slow Living Actually Means

Slow living isn’t about moving in slow motion or being lazy. It’s not about rejecting technology or abandoning ambition. It’s not about having unlimited time or money or the privilege of a life without demands. Slow living is about intentionality, about choosing quality over quantity, presence over productivity, meaning over momentum. It asks what we lose when we prioritize speed above all else, and whether those losses are worth the gains.

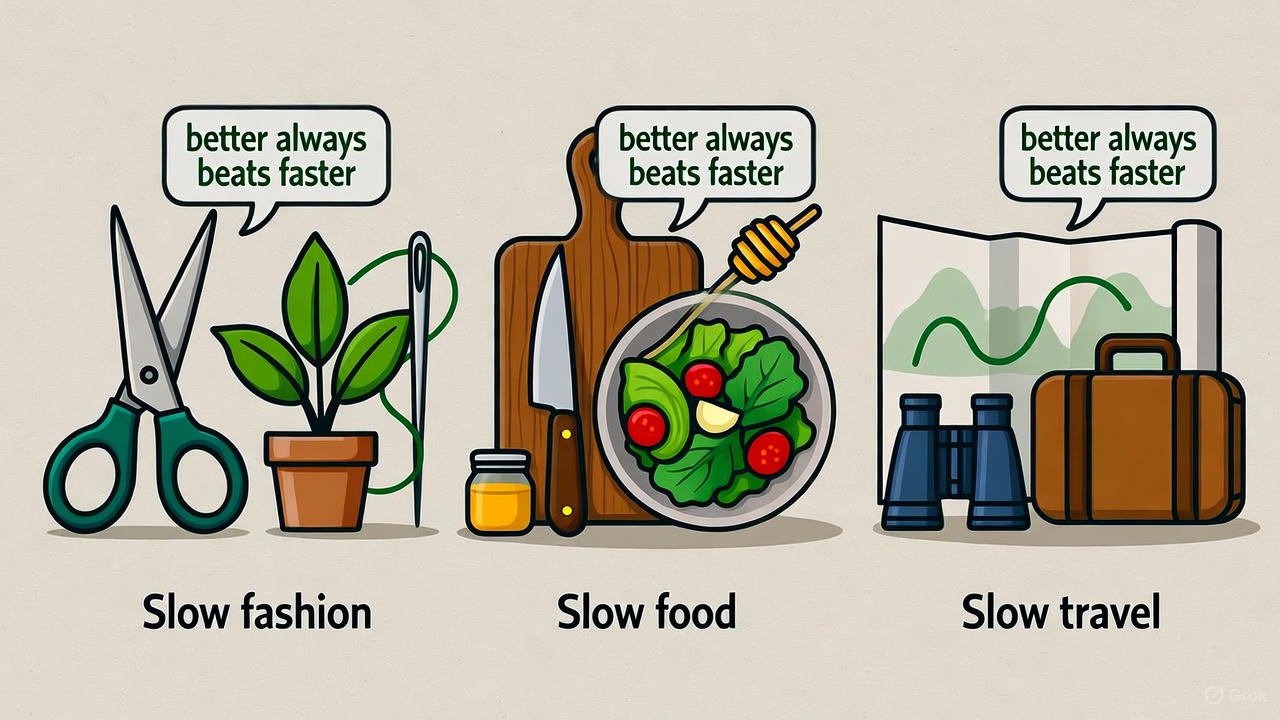

The slow movement started in Italy in the 1980s as “Slow Food,” a rebellion against fast food and the industrialization of eating. Italian journalist Carlo Petrini founded the movement in response to a McDonald’s opening near the Spanish Steps in Rome, but the philosophy quickly expanded beyond cuisine. What if meals were savored, not scarfed? What if food was grown with care, prepared with attention, eaten with presence? From there, the philosophy proliferated: slow fashion, slow travel, slow parenting, slow work, slow money. The common thread across all these domains is resistance to the pressure to speed up, choosing depth over breadth, valuing the process alongside the outcome.

Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, whose research on flow states has shaped our understanding of optimal experience, noted that the most meaningful moments in life usually involve a challenge that matches our skills, full engagement with the present, and a sense of time becoming irrelevant. Speed works against all of these conditions. When we’re rushing, we can’t fully engage. When we’re worried about the next thing, we can’t be present to the current thing. Slow living is an attempt to create the conditions where meaningful experience becomes possible, where life stops feeling like a blur of checkboxes and starts feeling like something you’re actually living.

The Cost of Constant Speed

Before talking about how to slow down, it’s worth acknowledging what speed has cost us. Our health suffers when we live in constant urgency. Stress researcher Robert Sapolsky has documented how chronic stress, the kind that comes from living in perpetual time pressure, damages nearly every system in the body. Elevated cortisol, compromised immune function, disrupted sleep, increased inflammation, our bodies weren’t designed for the relentless pace we subject them to. The health consequences of chronic rushing aren’t abstract future risks. They’re daily realities of fatigue, anxiety, and the vague sense that something is wrong even when you can’t name it.

Our relationships suffer when we’re too busy for deep conversation, too distracted for presence, too exhausted for genuine connection. Sherry Turkle, whose research at MIT focuses on technology and relationships, has documented how the constant fragmentation of attention erodes our capacity for the sustained engagement that intimacy requires. We’re physically present but mentally elsewhere, our attention always splitting toward the next demand. Our work quality suffers when we’re rushing, producing mediocre output because we don’t have time to think deeply, making poor decisions because reflection requires space we haven’t protected. And our sense of meaning suffers most of all. When you’re always rushing to the next thing, you miss the current thing entirely. Life becomes a series of tasks to complete rather than experiences to inhabit.

Slow Food: Returning to the Table

Let’s start with food, because it’s where most people can feel the difference immediately. Fast food culture taught us that eating is fuel, something to do quickly, cheaply, and without thought. Slow food culture says eating can be sacred, an act of nourishment, pleasure, and connection. Not every meal needs to be a three-hour event, but the complete absence of presence around eating represents a profound loss.

Cooking from scratch, not because you’re aspiring to be a chef but because the act of preparing food can be meditative, offers one entry point. Chopping vegetables, stirring a pot, tasting as you go, these actions ground you in sensory experience and pull you out of the mental chatter that dominates most waking hours. Eating without screens represents another shift, removing the phone, turning off the TV, and being present to the food, maybe to conversation, definitely to the simple act of nourishing yourself. Michael Pollan, whose writing has explored our relationship with food across multiple books, suggests that the industrialization of eating has separated us from one of the most fundamental human experiences. Slow food is a way of reclaiming that connection.

Savoring rather than scarfing, chewing slowly, tasting flavors, noticing textures, letting your body register fullness before overeating, transforms the physical experience of eating. When possible, sourcing with care, buying from local farmers, supporting sustainable agriculture, knowing where your food comes from, adds another dimension. And sharing meals, eating together with presence and intention, builds connection in ways that nothing else quite replicates. You don’t have to do all of this for every meal. But try eating one meal this week, just one, with full presence. Notice the difference.

Slow Work: Depth Over Busyness

The workplace worships speed: faster turnarounds, instant responses, more output in less time. But Cal Newport, whose book “Deep Work” has influenced how many knowledge workers think about their time, argues that constant speed actually reduces quality. The best cognitive work requires sustained attention, and sustained attention is incompatible with the fragmentation of constant rushing. Deep work blocks, dedicated uninterrupted time for cognitively demanding tasks, represent one approach to slow work. Single-tasking, doing one thing fully instead of ten things poorly, represents another.

Strategic pauses, taking breaks to think and reflect rather than powering through, often produce better results than relentless grinding. Gloria Mark’s research at UC Irvine found that workers who take regular breaks show better performance than those who push through continuously. Saying no, protecting your time and energy by declining non-essential commitments, creates the space that slow work requires. The practice of single-tasking embodies this slow work philosophy: doing one thing fully instead of many things poorly. The irony is that slow work often produces better results faster because you’re not constantly context-switching, redoing mistakes caused by rushed attention, or burning out in ways that tank your productivity for days afterward. For more on protecting focus in a distracted world, see our piece on deep work practices.

The Privilege Question

Here’s the objection that slow living inevitably raises: isn’t this a privilege? Isn’t slowness a luxury for people who don’t have bills, responsibilities, and the relentless pressure of making ends meet? The concern is legitimate. Slow living is harder when you’re working multiple jobs, raising kids alone, or living paycheck to paycheck. Systemic inequality makes slowness genuinely inaccessible for many people, and any honest discussion of slow living has to acknowledge this.

But here’s the nuance: slow living isn’t all-or-nothing. You don’t have to quit your job, move to the countryside, or hand-make everything to incorporate slowness into your life. Eating one meal a week without screens doesn’t require wealth. Taking a different route home and actually noticing your surroundings costs nothing. Buying one high-quality item instead of three cheap ones often costs the same in the long run. Spending one hour a week doing something with no purpose except joy is possible for more people than the constant-busy narrative suggests. Slow living isn’t a lifestyle overhaul or an identity you adopt wholesale. It’s a series of small choices toward presence and quality, available in varying degrees to most people, even if the full expression remains out of reach.

Your Invitation

We’ve internalized the message that busy equals important, that rest is laziness, that slowing down means falling behind. But what if the opposite is true? What if slowing down helps you catch up, to yourself, to your values, to the life you’re actually living rather than racing through? You don’t need permission to slow down, but if you feel like you do: here it is. You’re allowed to do less. You’re allowed to say no. You’re allowed to choose depth over breadth, quality over quantity, presence over productivity. You’re allowed to opt out of the race and walk at your own pace. For a deeper exploration of why rest isn’t laziness, see our piece on the rest revolution.

This week, choose one area to experiment with slowness. Eat one meal mindfully, without screens, tasting what you eat. Repair something instead of replacing it, engaging with the object rather than discarding it. Protect one hour of focused, uninterrupted work time, and notice what quality emerges. Do one thing you love with no purpose or productivity attached. Notice how it feels. Notice what changes in you when you’re not rushing. Slow living won’t fix everything. But it will help you remember that life isn’t a race to the finish line. It’s the only life you get. You’re allowed to actually experience it.

Sources: Carl Honore’s “In Praise of Slowness,” Carlo Petrini’s Slow Food movement, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s flow research, Cal Newport’s “Deep Work,” Robert Sapolsky’s stress research.