You sit down to work on the thing that actually matters. Five minutes in, a Slack message. Ten minutes later, an email. Fifteen minutes after that, a notification from something you don’t even remember signing up for. An hour passes, and you’ve accomplished almost nothing substantial. You’ve been busy, certainly. You’ve responded to things, attended to things, moved things around. But the important work, the work that would actually move your life or career forward, remains untouched.

Welcome to the modern knowledge worker’s reality: endless shallow work punctuated by brief, futile attempts at focus. But here’s what most people don’t realize. The ability to focus deeply, what Cal Newport calls “deep work,” is becoming both rarer and more valuable in exactly inverse proportion. In a world optimized for distraction, deep focus is a superpower. And unlike many superpowers, this one can be cultivated through deliberate practice.

Understanding Deep Work

Deep work is professional activity performed in a state of distraction-free concentration that pushes your cognitive abilities to their limit. It’s when you’re fully immersed in a complex task, writing, coding, designing, strategizing, creating, and time seems to disappear. Hours feel like minutes. You enter what psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi calls “flow state.” You produce your best work, the kind of work that builds careers and creates lasting value.

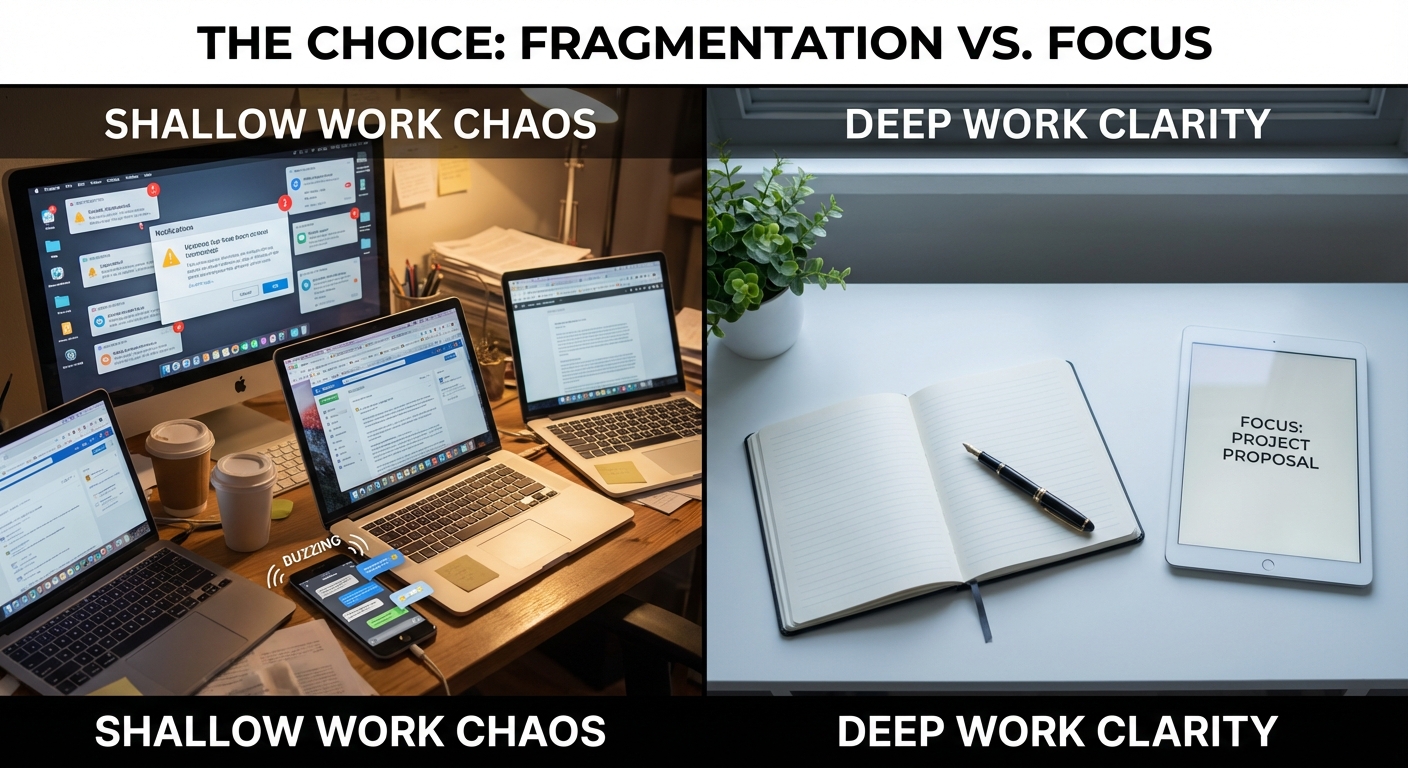

The opposite is shallow work: low-cognitive tasks performed while distracted. Responding to emails, attending meetings without clear agendas, scrolling through documents, processing administrative busywork. Shallow work is necessary; someone has to answer the emails and attend the meetings. But shallow work is not sufficient. It’s the baseline, not the differentiator. Deep work is where breakthroughs happen, where real value is created, where you actually move the needle on things that matter.

Cal Newport, computer science professor at Georgetown and author of “Deep Work,” argues that the ability to perform deep work is becoming increasingly rare at exactly the same time it’s becoming increasingly valuable in our economy. The skills that matter most, complex problem-solving, creative synthesis, strategic thinking, all require sustained focus to develop and deploy. But our work environments, our technologies, and our habits are all conspiring against that focus.

Why Deep Work Has Become So Rare

Our work environments are designed, often unintentionally, to prevent deep work. Open offices create constant visual and auditory distraction; you can’t enter deep focus when your peripheral vision catches every person walking by and your ears catch every nearby conversation. Notification culture trains us to expect and provide immediate responses to everything, making it feel transgressive to be unreachable even for an hour. Meeting overload fragments our days into 30-minute chunks where nothing substantive can happen because deep work requires time to warm up and time to sustain.

Gloria Mark, a professor at UC Irvine who studies workplace attention, found that the average knowledge worker is interrupted or switches tasks every three minutes. After an interruption, it takes an average of 23 minutes to fully return to the original task. Do the math: if you’re interrupted every three minutes, you’re never reaching full focus. You’re perpetually in shallow mode, skimming the surface of your cognitive potential. And here’s the insidious part: shallow work feels productive because it’s busy. You’re responding, you’re attending, you’re processing. But busy isn’t the same as effective. Most knowledge workers haven’t had a single four-hour block of uninterrupted focus in months. That’s not a personal failing. It’s a systemic problem. But it’s also a systemic problem you can opt out of.

Creating Protected Time

To do deep work, you need time protected from interruption. This sounds obvious, but implementing it requires swimming against the current of modern work culture. You have to actually defend your attention, which means treating it as the scarce resource it is.

Cal Newport recommends time blocking: scheduling deep work blocks like you’d schedule a meeting, as non-negotiable time on your calendar that others can see but can’t book over. For a detailed guide to this practice, see our piece on time blocking. Start with 90-minute blocks; most people can sustain deep focus for 60 to 120 minutes before needing a break. Schedule them during your peak energy hours, which vary by individual. If you’re a morning person, protect 9 to 11 AM. If you’re a night owl, guard your evening hours. The key is matching your hardest cognitive work to your highest cognitive capacity.

Batch your shallow work into designated times. Instead of answering emails throughout the day, designate specific windows, perhaps 11 AM and 4 PM, when you process communications and administrative tasks. This keeps shallow work from metastasizing into the entire day while still ensuring things get handled. Aim for three to four hours of deep work daily; that’s the realistic maximum for most people, and it’s more than most knowledge workers currently achieve. If you can consistently hit three hours of genuine deep focus per day, you’ll outproduce colleagues who work twice as many hours in fragmented shallow mode.

Protecting Your Environment

Your environment either supports deep work or sabotages it. There’s no neutral. Digital distractions are the obvious culprit. Every notification, every open browser tab, every Slack ping is an invitation to fragment your attention. The solution has to be blunt because willpower alone isn’t enough. Turn everything off during deep work blocks. All notifications. Email closed. Slack closed. Phone in another room or on airplane mode. If you find yourself reaching for distractions anyway, use website blockers like Freedom or Cold Turkey to make distraction temporarily impossible.

Signal your unavailability to others. If you’re in an office, close your door. Wear headphones even if you’re not listening to anything; they communicate “don’t interrupt.” Set your Slack status to something clear: “Deep work until 2 PM.” Let your team know your deep work schedule so they can plan around it. Most people will respect focused time once they understand the pattern; they just need to know what the pattern is. Prepare your physical space to eliminate any excuse to break focus. Declutter your desk; physical clutter creates mental clutter. Have good lighting and comfortable temperature. Keep everything you need within reach. You shouldn’t have to get up to find a pen or adjust anything. Set yourself up completely, then disappear into the work.

Building Your Capacity

Like physical fitness, focus capacity grows with training. If you haven’t done deep work in a while, you won’t be able to sustain it for hours immediately. That’s normal. Start where you are. If you can only focus for 20 minutes before the urge to check something becomes overwhelming, start there. Add 10 minutes each week. Within a few months, you’ll be able to sustain focus for 90 minutes or more.

Reduce constant stimulation throughout your day, not just during deep work blocks. The more you context-switch, the harder deep focus becomes. Practice monotasking even during shallow work; do one thing at a time rather than bouncing between tabs and tasks. This trains your attention muscles for when you need them most. Embrace boredom as a feature, not a bug. When you’re waiting in line, don’t automatically reach for your phone. Let your mind wander. You’re training your brain that discomfort is survivable, that you don’t need constant stimulation to function. This tolerance for boredom is what makes sustained focus possible. Our guide to presence in a distracted world explores this practice further.

And schedule real downtime. Your brain needs recovery to do its best work. Walks, exercise, adequate sleep, and genuine rest, time when you’re not consuming or producing, make deep work sustainable. Csikszentmihalyi’s research on flow shows that the highest performers aren’t grinding constantly; they alternate between intense focus and genuine recovery. For more on sustainable energy management, see our piece on working with your body’s natural rhythms.

Choosing What Deserves Depth

Not everything deserves deep work. This is critical to understand. Deep work is a finite resource, you have maybe three to four hours of it per day. Spending it on the wrong things is waste. Reserve deep work for high-value, cognitively demanding tasks: strategic planning that shapes your direction, complex problem-solving that others can’t easily do, creative work like writing or design or coding where quality depends on sustained attention, learning difficult new skills that will compound over time, crafting important communications or proposals where the stakes are high.

Don’t waste deep work on routine administrative tasks, most emails, status update meetings, or low-stakes decisions. Those things need to happen, but they don’t need your best cognitive resources. Batch them into shallow work sessions and move through them efficiently. The question isn’t “Can I do this deeply?” It’s “Does this deserve my limited deep work capacity?” Be ruthlessly selective. Protect your best hours for work that actually matters, the work that builds your career and creates results you’re proud of.

Your Invitation

This week, protect one 90-minute block for deep work. Just one. Turn off everything. Close the door, literally or figuratively. Set a clear goal for what you want to accomplish. Sit with the discomfort of the first 10 to 15 minutes when your brain begs for distraction. Push through. Do the work.

Notice how it feels. Notice what you produce. Notice the difference between this and your usual fragmented working day. Then do it again tomorrow. And the day after that.

Deep work isn’t a luxury. In a shallow world, it’s how you create work that matters and a life that feels meaningful. The ability to focus without distraction on a cognitively demanding task is becoming rare. Which means, if you can cultivate it, you’ll have something increasingly valuable. Something most people can’t or won’t develop. Something that compounds over time.

Start with one block. See what happens.

Sources: Deep Work (Cal Newport), Flow Theory (Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi), Workplace Attention Research (Gloria Mark, UC Irvine).