The presentation is three weeks away, but you’ve already run through it in your mind forty times. You’ve imagined forgetting your points, stumbling over words, watching your audience’s faces cloud with boredom or confusion. You’ve rehearsed the aftermath: the awkward silence, the polite non-comments, the private certainty that everyone saw through you.

None of this has happened. The presentation hasn’t even been written yet. But your body doesn’t seem to know that. Your chest tightens when you think about it. Your sleep is disrupted by scenarios that exist only in your imagination. You’re living in a future that may never arrive, and it’s exhausting.

This is anticipatory anxiety, and according to recent research, it’s one of the primary drivers of anxiety disorders. The good news is that understanding how it works opens up pathways for interrupting it. The worry loop that feels so automatic, so inevitable, is actually something you can learn to step out of.

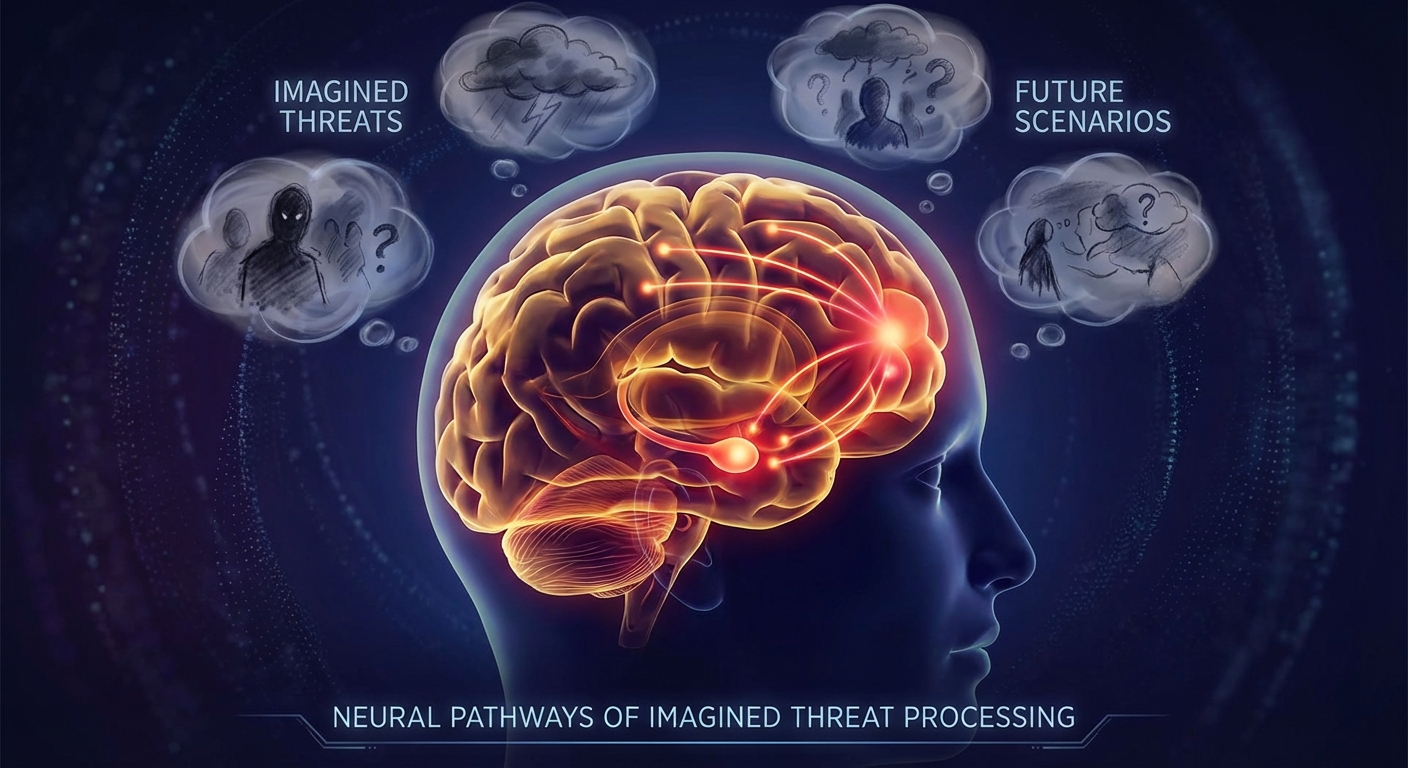

The Neuroscience of Future Fear

Your brain evolved to anticipate threats. This was useful when threats were immediate and physical: a rustle in the grass that might be a predator, a shift in weather that might bring danger. The ability to imagine future scenarios and prepare for them gave our ancestors a survival advantage.

The problem is that this same system now responds to modern threats, which are often abstract, distant, and uncertain, with the same intensity it once reserved for tigers. A difficult conversation next week, a performance review next month, the general uncertainty of the future: your nervous system can treat these as emergencies requiring immediate response, even when there’s nothing you can actually do about them right now.

Research published in Nature Reviews Neuroscience identifies five processes essential for adaptive responses to uncertain future threats. When these processes malfunction, the result is pathological anxiety. At the core is intolerance of uncertainty: the brain’s difficulty tolerating the simple fact that we don’t know what will happen.

According to a study in Frontiers in Psychology, future anxiety refers to a state of worry, uncertainty, fear, and concern about negative changes in the future. Although the fear experienced is clear and conscious, it stems from cognitive representations of future events rather than actual events. The fear is experienced here and now but refers to things that haven’t happened yet.

How Worry Becomes a Loop

The mechanics of anticipatory anxiety help explain why it can feel so hard to escape. When you imagine a threatening future scenario, your body responds as if the threat is real. Stress hormones are released, muscles tense, attention narrows. This physical response then becomes evidence to your brain that something is indeed wrong, which intensifies the worry, which intensifies the physical response.

Research from the American Psychological Association describes this pattern during key life transitions, noting that anticipatory anxiety often peaks when people face uncertainty about major changes: starting a new job, moving to a new city, entering or leaving a relationship.

The loop is sustained by avoidance, both behavioral and cognitive. When you avoid the thing you’re anxious about, you never get evidence that it might be okay. When you engage in worry as a form of mental preparation, you feel like you’re doing something productive, but you’re actually just rehearsing failure scenarios without gaining any useful skills or information.

Research shows that behavior and thoughts, including worry, prevent anxious individuals from being exposed to evidence that might contradict their negative predictions about the future. The worry feels protective, but it actually perpetuates the anxiety by keeping you locked in hypothetical scenarios rather than engaged with reality.

The Paradox of Control

At its root, anticipatory anxiety often reflects a desperate attempt to control the uncontrollable. If you can just think through every possible scenario, if you can just prepare for every contingency, maybe you can protect yourself from bad outcomes. The mind treats worry as a form of problem-solving, as if thinking about something enough times will eventually yield a solution.

But many sources of anxiety aren’t actually problems to be solved. They’re uncertainties to be tolerated. The presentation might go well or it might go poorly; no amount of advance worrying changes the probability. The job interview will unfold however it unfolds; your nervous rehearsal at 3 AM doesn’t improve your chances.

This is where intolerance of uncertainty becomes central. Supporting studies show that intolerance of uncertainty constitutes the core feature of anxiety and worry. People who struggle most with anticipatory anxiety often have difficulty accepting that the future is inherently unknown, that control is always partial, that some things cannot be prevented through mental effort alone.

What the Research Says Works

The evidence points toward several effective approaches for managing anticipatory anxiety. These aren’t quick fixes, but they target the mechanisms that keep the worry loop spinning.

Building tolerance for uncertainty. Treatment approaches that specifically address intolerance of uncertainty show strong results. This involves gradually exposing yourself to uncertain situations without engaging in your usual worry or avoidance behaviors. Over time, you learn that uncertainty itself isn’t dangerous, that you can handle not knowing, that the catastrophes your mind predicts rarely materialize.

Returning to the present. When you’re caught in future-focused worry, your attention has time-traveled away from your actual life. Mindfulness practices train the capacity to notice when this has happened and to return attention to present-moment experience. A simpler strategy, researchers note, involves encouraging people to spend less time worrying about what might come and instead focus on life in the present. Complete absorption in the present moment obviates anxiety about the future.

Distinguishing productive from unproductive worry. Some worry is useful: it identifies real problems and motivates practical action. But most anticipatory anxiety involves going over the same ground repeatedly without reaching any new conclusions or taking any helpful action. Learning to recognize when worry has stopped being productive, and choosing to disengage at that point, is a learnable skill.

Challenging catastrophic predictions. Anxious thinking tends toward worst-case scenarios. Cognitive approaches involve examining these predictions more carefully: How likely is this outcome, really? What’s the evidence for and against? What would you say to a friend who was predicting the same catastrophe? This doesn’t mean convincing yourself everything will be fine; it means returning to realistic assessment rather than anxiety-driven distortion.

The Role of Belonging

An intriguing line of research connects anticipatory anxiety to a more fundamental need: belonging. A study published in PMC found that while the feeling of being loved, respected, and having a sense of belonging forms a crucial foundation for psychological health, the lack of belonging can intensify feelings of rejection, isolation, and alienation, leading to anxiety about both present and future life.

This suggests that anticipatory anxiety isn’t just about the specific thing you’re worried about. It’s often connected to deeper concerns: Will I be accepted? Will I be able to handle what comes? Am I fundamentally okay? When these questions feel uncertain, the mind attaches that uncertainty to specific future events, creating the sense that the presentation, the interview, or the transition is the source of the anxiety rather than a surface expression of something deeper.

Building genuine connection and a stable sense of belonging won’t eliminate all anticipatory anxiety, but it can reduce the intensity of the baseline uncertainty that makes specific worries feel so threatening.

Practical Steps for Breaking the Loop

When you notice anticipatory anxiety arising, these research-informed strategies can help interrupt the pattern.

Name what’s happening. “I’m having anticipatory anxiety about the meeting” is different from “The meeting is going to be terrible.” The first acknowledges the anxiety as a mental event; the second treats the feared outcome as fact. This simple naming of your experience creates a bit of distance from the worry.

Set a worry time. This counterintuitive technique involves postponing worry to a specific time of day rather than letting it intrude whenever it wants. When anxious thoughts arise, you note them and commit to addressing them later, during your designated 15 minutes of worry time. Many people find that when worry time arrives, the concerns feel less urgent, and the act of postponing demonstrates that you have some choice about when and how much you engage with worry.

Ask the utility question. Is this worry helping me prepare for something I can actually influence, or am I just rehearsing scenarios I can’t control? If worry is generating useful action, like making a list of points to cover in a presentation, it’s serving a purpose. If it’s just cycling through catastrophes, it’s time to disengage.

Move your body. Anticipatory anxiety lives in the body as well as the mind. Physical movement, especially anything that engages your senses and requires attention, can interrupt the mental loop. A walk, some stretching, even just standing up and changing your physical position can shift your state enough to create space for a different response.

Practice micro-moments of presence. You don’t need to meditate for an hour to experience the present moment. Taking three conscious breaths, feeling your feet on the floor, noticing five things you can see right now: these brief returns to presence can be sprinkled throughout the day, gradually building your capacity to be here rather than lost in future fears.

Your Invitation

The future will always be uncertain. That’s not a problem to be solved; it’s a feature of being human. No amount of worry will make the unknown known, will guarantee good outcomes, or will protect you from the possibility of difficulty.

What you can develop is your relationship to uncertainty. You can learn to tolerate not knowing, to trust your capacity to handle what comes, to spend less of your precious present caught in futures that may never arrive.

This doesn’t mean being reckless or ignoring legitimate concerns. Plan when planning is useful. Prepare when preparation helps. But notice when worry has stopped serving you, when it’s become a loop that generates suffering without producing solutions.

The presentation is three weeks away. You could spend those weeks in anxious rehearsal of imagined failures. Or you could do the actual preparation that’s useful, and then practice being here, in this day, in this moment, where the presentation isn’t happening and where your life actually is.

The science of being present isn’t about denying the future or pretending uncertainty doesn’t exist. It’s about recognizing that the only time you can actually live is now. The anxious mind keeps insisting that you need to be somewhere else, worrying about something that hasn’t happened. But you don’t. You can be here. You can return, again and again, to the only moment that’s actually real.

The worry will likely come back. That’s okay. You don’t have to win a permanent victory over anticipatory anxiety. You just need to keep noticing when you’ve time-traveled into future fears, and keep choosing to return to now. Each return is practice. Each return makes the next one a little easier. And gradually, the grip of imagined futures loosens, making room for the life that’s actually happening.

Sources: Nature Reviews Neuroscience, Frontiers in Psychology, American Psychological Association, PMC on intolerance of uncertainty, PMC on belonging and anxiety.