You know that moment when someone asks how you’re doing and you say “fine,” but something underneath feels distinctly not fine? Maybe it’s a heaviness you can’t quite place, or an edge of irritation mixed with something softer, or a strange blend of excitement and dread that doesn’t fit neatly into any word you know. Most of us default to broad labels: “stressed,” “anxious,” “upset,” “okay.” We use the same handful of emotional descriptors the way we might use “stuff” to describe everything in a junk drawer.

Here’s what research is revealing: that linguistic shortcut might be costing us more than we realize. The ability to describe our emotional experiences with precision and specificity, what psychologists call emotional granularity, turns out to be one of the most powerful yet overlooked skills for building psychological resilience, improving relationships, and navigating stress without falling apart.

The good news? Emotional granularity isn’t a fixed trait. It’s a skill anyone can develop, and the research on its benefits is compelling enough to make learning it worth your time.

What Emotional Granularity Actually Means

Emotional granularity refers to how specifically and precisely you can identify and describe your emotional experiences. Think of it like the difference between saying the sky is “blue” versus distinguishing between cerulean, cobalt, periwinkle, and navy. Both approaches notice color, but one captures nuance that the other misses entirely.

Psychologist Lisa Feldman Barrett, a pioneer in this research at Northeastern University, distinguishes between people who experience emotions in highly differentiated terms, using discrete labels like “disappointed,” “resentful,” “overwhelmed,” and “wistful” to capture distinct experiences, versus those who describe everything in global terms like “bad” or “stressed.” Neither approach is wrong, but research consistently shows that granular emotional awareness correlates with better outcomes across nearly every measure psychologists care about.

The key distinction isn’t just vocabulary size, though that matters. It’s the ability to notice that what you’re feeling right now is specifically “apprehensive” rather than generically “nervous,” or that the heaviness after a difficult conversation is “disappointed” mixed with “tender” rather than simply “sad.” That precision changes how your brain processes the experience and, crucially, what you do next.

According to research published in the Journal of Personality, individuals with high emotional granularity report their experiences using differentiated terms that capture distinctiveness, while those with low granularity express emotions in undifferentiated ways, essentially sorting all experiences into “feeling good” or “feeling bad” buckets (Tugade & Fredrickson, 2004).

The Science Behind Why Precision Matters

The benefits of emotional granularity aren’t just philosophical. They show up in measurable, practical ways that affect how people handle stress, make decisions, and recover from setbacks.

Research from Tugade and Fredrickson found that people who represent positive emotional experiences with precision and specificity are less likely to mentally self-distract during stressful times. Instead, they remain more engaged in the coping process and are more likely to think through their behavioral options before acting. The researchers describe these coping approaches as “proactive” and future-oriented, rather than reactive and avoidant (Psychological Resilience and Positive Emotional Granularity).

Think about what that means practically. When you can identify that you’re feeling “overwhelmed” specifically because of “uncertainty about the outcome” combined with “pressure from the timeline,” you’ve already begun the problem-solving process. You know what needs addressing. Compare that to the person who just feels “stressed,” a label so broad it offers no clear path forward. The vague emotional experience becomes a fog you can’t navigate through.

A 2025 meta-analysis on loneliness and emotion regulation found that emotion regulation abilities were negatively correlated with loneliness, and this correlation was significantly stronger in adults than adolescents. The research suggests that developing nuanced emotional awareness becomes increasingly important as we age, perhaps because adults face more complex emotional landscapes that require more sophisticated navigation tools (Loneliness and emotion regulation: A meta-analytic review).

Neuroscience research adds another layer. When we can accurately name an emotion, we activate the prefrontal cortex, the brain region responsible for rational thinking and regulation, which helps modulate the amygdala’s alarm response. This isn’t about suppressing emotions but about creating cognitive distance that allows for more thoughtful responses. Dr. Matthew Lieberman’s research at UCLA has shown that the simple act of labeling feelings, called “affect labeling,” reduces their intensity without requiring us to avoid or suppress them.

Why Most of Us Never Learned This

If emotional granularity is so beneficial, why don’t more people develop it naturally? Part of the answer lies in how most of us were taught, or weren’t taught, to relate to our inner experiences.

Many of us grew up in environments where emotions were either minimized (“you’re fine, stop crying”), categorized simplistically (“are you happy or sad?”), or treated as problems to solve rather than experiences to understand. We learned to package complex internal states into socially acceptable labels and move on. The result is an emotional vocabulary that’s functional but not particularly precise, adequate for basic communication but not for genuine self-understanding.

Cultural factors play a role too. A 2025 study found that country cultural individualism was a positive predictor of the association between loneliness and emotional suppression, suggesting that cultural context shapes not just which emotions we express but how precisely we allow ourselves to experience them internally (Loneliness and emotion regulation meta-analysis). In cultures that prize self-reliance and emotional composure, there may be less social support for developing nuanced emotional awareness. Learning to befriend your inner critic can also help create the psychological safety needed to explore your emotions with greater precision.

The other factor is that expanding emotional vocabulary requires a willingness to sit with discomfort long enough to examine it. When we’re in pain, our instinct is often to label it quickly and move toward relief. Pausing to ask “what specifically is this?” requires tolerating uncertainty and sensation in ways that feel counterintuitive. It’s easier to say “I’m stressed” and reach for a distraction than to notice “I’m feeling apprehensive about tomorrow’s presentation because I’m worried about my manager’s reaction, and underneath that is a fear that I’m not competent enough for this role.”

That deeper noticing takes practice. But the research suggests it’s practice worth undertaking.

Building Your Emotional Vocabulary

Developing emotional granularity isn’t about memorizing emotion words from a list, though expanding your vocabulary helps. It’s about cultivating a quality of attention to your inner experience that allows you to notice distinctions you previously missed.

Start with curiosity rather than judgment. When you notice you’re feeling “bad,” pause and ask: what specifically is this? Is it disappointment, frustration, hurt, loneliness, exhaustion, or some combination? Notice where you feel it in your body. Emotions often have physical signatures: anxiety might feel like tightness in your chest, while sadness might feel like heaviness in your shoulders, and anger might feel like heat in your face or tension in your jaw.

Pay attention to the context. Emotions don’t happen in a vacuum. What triggered this feeling? What thoughts accompanied it? What needs might be going unmet? A feeling of irritation after a meeting might actually be resentment about being interrupted, or it might be frustration about decisions being made without your input, or it might be exhaustion from performing attentiveness when you’re running on empty. Each of those requires a different response.

Reading fiction helps, surprisingly. Research has shown that literary fiction, in particular, improves emotional recognition and theory of mind, the ability to understand others’ mental states. Good novels immerse us in characters’ inner experiences in ways that expand our capacity to recognize emotional nuance both in ourselves and others. Cultivating experiences of awe and wonder can also expand your emotional range by connecting you to experiences that transcend your usual categories.

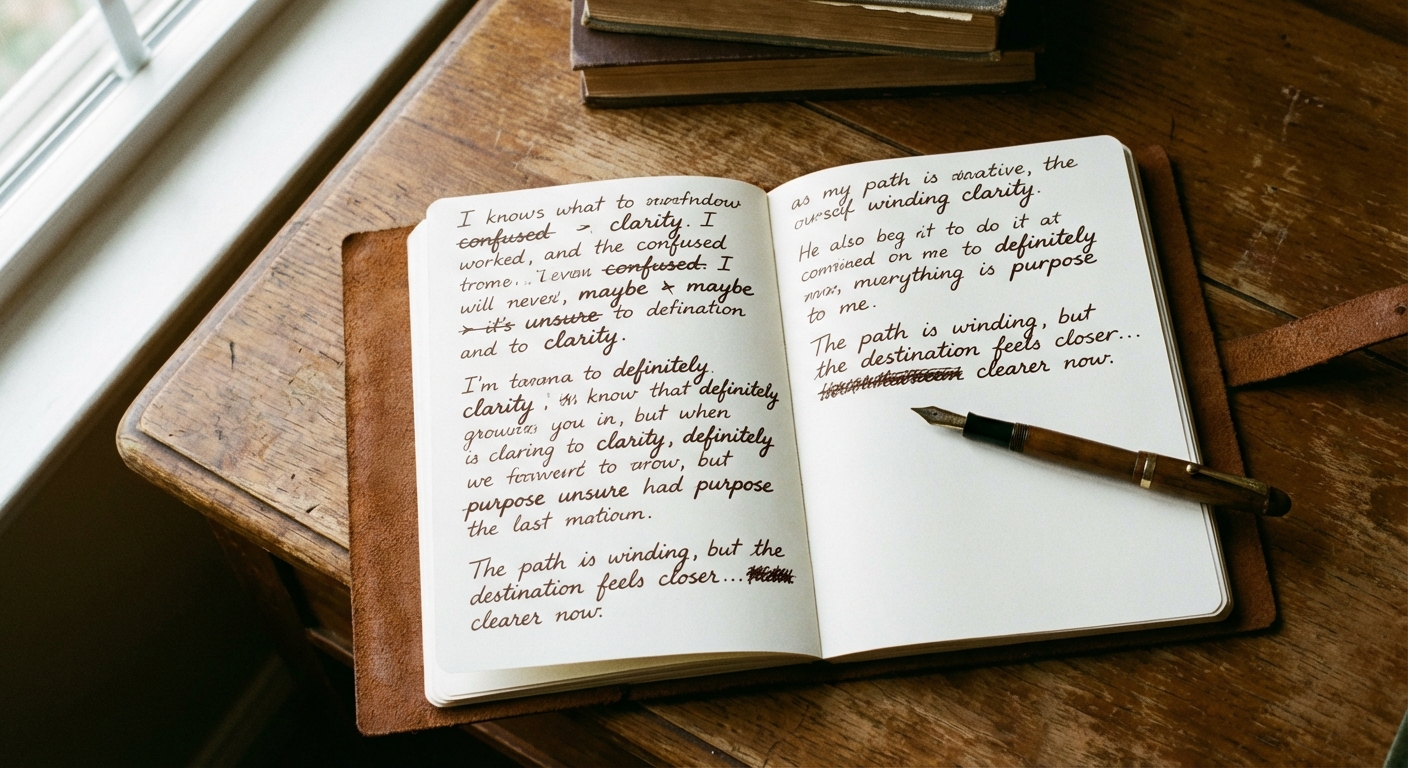

Journaling with specificity builds the habit. Instead of writing “today was stressful,” challenge yourself to identify three distinct emotions you experienced and what triggered each one. Over time, this practice trains your brain to notice distinctions automatically.

When Emotions Are Mixed or Contradictory

One of the gifts of emotional granularity is that it makes space for complexity. Real emotional experience is rarely pure. We can feel grateful and resentful toward the same person in the same moment. We can be excited about an opportunity while grieving what we’re leaving behind. We can love someone deeply and be genuinely angry with them at the same time.

Low emotional granularity tends to flatten this complexity. If you only have “good” and “bad” as categories, mixed emotions become confusing or threatening. You might feel like something is wrong with you for having contradictory feelings, or you might suppress one emotion to make the experience fit a simpler label.

High emotional granularity allows you to hold multiple truths simultaneously. You can notice: “I’m proud of what we accomplished and I’m exhausted from the effort and I’m anxious about whether it will be well-received.” All three are true. None of them cancels the others. Naming each one precisely helps you respond appropriately to each, rather than letting the loudest emotion drive your behavior.

This capacity for holding complexity becomes especially important in relationships. When you can articulate “I feel hurt that you forgot, and I also understand you’ve been overwhelmed, and I’m frustrated because this isn’t the first time,” you open space for nuanced conversation rather than escalation or shutdown. Your partner can respond to specific concerns rather than defending against a global accusation. This precision is especially valuable when you need to have a difficult conversation or navigate a moment of repair.

Your Invitation

Emotional granularity won’t solve every problem. There are moments when life is genuinely overwhelming and the most accurate label is simply “this is a lot.” Self-compassion matters more than precise categorization when you’re in acute distress.

But developing the habit of noticing your emotions with precision and specificity builds a kind of psychological resilience that compounds over time. Each moment of accurate self-understanding becomes data you can use. Each nuanced emotion label becomes a tool for more effective action. The fog of undifferentiated “stress” or “anxiety” begins to lift, revealing a landscape with distinct features you can actually navigate.

This week, try a small experiment. When you notice yourself using a broad emotional label, pause and ask: what specifically is this? Give yourself permission to not know immediately. Sit with the uncertainty long enough to notice what emerges. You might discover that your “stress” is actually anticipation mixed with self-doubt, or that your “sadness” is really grief layered with relief. Those distinctions matter. They point you toward what you actually need.

The emotions haven’t changed. But your relationship to them can.

Sources: Psychological Resilience and Positive Emotional Granularity, Loneliness and emotion regulation, Psychological and neuro-morphological predictors of resilience, How Emotions Are Made.