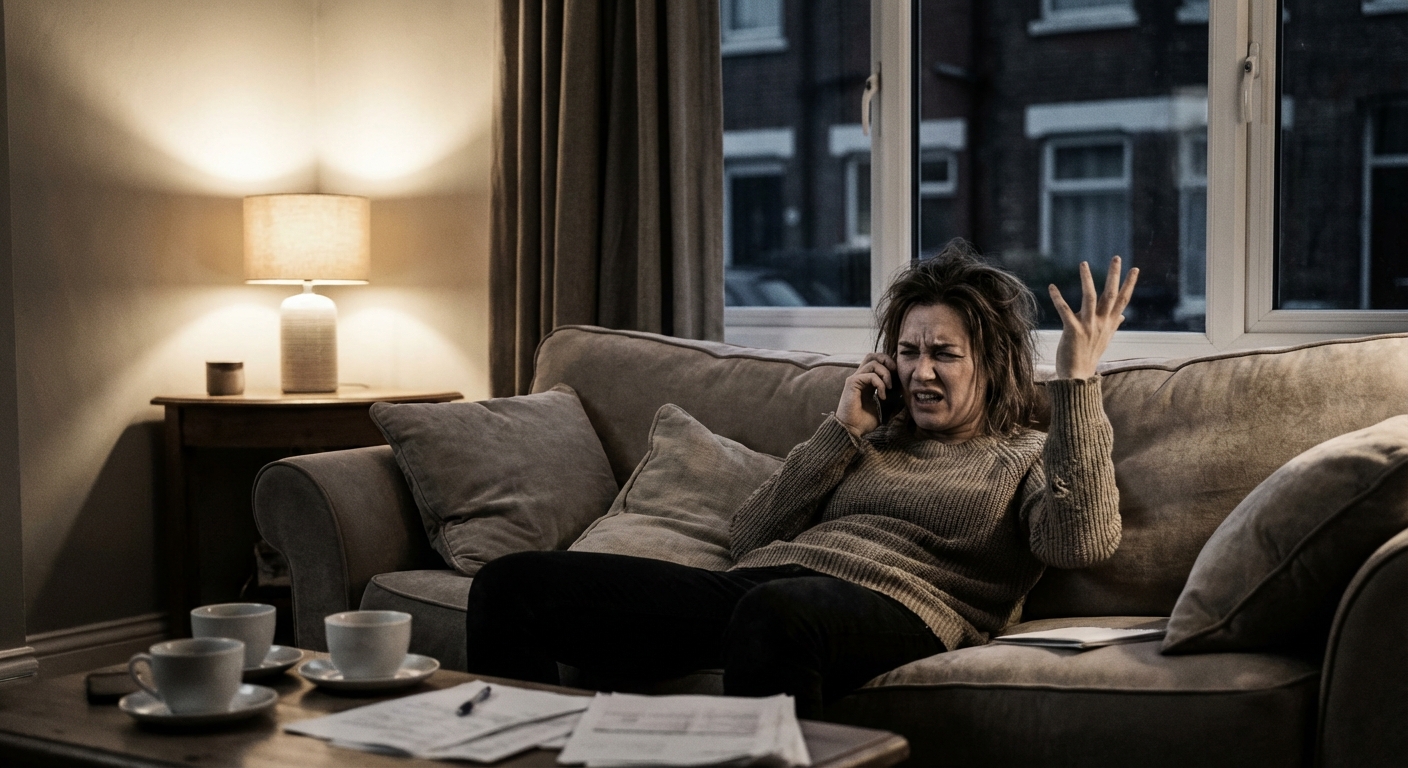

You’ve had the conversation. You call your best friend to unload about your impossible coworker, your frustrating partner, your latest disappointment. Forty-five minutes later, you hang up feeling somehow worse than before. The frustration hasn’t lifted; it’s calcified. You’ve rehearsed every grievance so thoroughly that you’re now more convinced than ever that everything is terrible.

Then there are the other conversations. The ones where you start tangled and confused, where talking helps you find the thread, where you hang up feeling lighter, clearer, more able to move forward. Same friend, same problems, different outcome.

The difference isn’t random. Research on emotional processing reveals that venting can either help us work through feelings or trap us in them. Understanding which is which might be the most practical relationship skill you develop this year.

The Difference Between Processing and Spiraling

Psychologist James Pennebaker has spent decades studying how talking and writing about difficult experiences affects our wellbeing. His research reveals a counterintuitive finding: simply expressing negative emotions doesn’t reliably make us feel better. What matters is how we express them.

Processing involves making sense of an experience. It’s not just reporting what happened; it’s examining why it bothered you, what it means, and what you might do about it. When we process effectively, we use words that indicate insight, causation, and realization. Phrases like “I just realized,” “I think what’s really going on is,” or “This reminds me of” signal that we’re making connections, not just venting steam.

Spiraling, by contrast, is emotional repetition without movement. We tell the same story with the same outrage, reinforcing the original emotional response rather than transforming it. Each retelling strengthens the neural pathways associated with that frustration or hurt. We’re practicing being upset.

Researchers call the harmful version “co-rumination,” a pattern especially common in close friendships where two people repeatedly discuss problems, speculate about causes, and focus on negative feelings without moving toward resolution. Studies on co-rumination have found that while it can strengthen the sense of intimacy between friends, it’s also associated with increased anxiety and depression over time. The closeness feels good; the emotional amplification doesn’t.

Signs Your Venting Isn’t Working

How do you know if you’re processing or spiraling? A few markers can help you recognize when talking has stopped helping.

The repetition test is the simplest. If you’ve told the same story more than three times without any new insight or perspective emerging, you’re likely reinforcing the wound rather than healing it. Processing tends to evolve; spiraling stays stuck. Notice whether each conversation adds something new or simply replays the same recording.

Pay attention to your energy afterward. Genuine emotional processing typically leaves you feeling slightly tired but clearer, like you’ve completed some internal work. Spiraling leaves you activated, agitated, still buzzing with unresolved feeling. If you hang up and immediately want to call someone else to vent more, that’s a sign the conversation didn’t do what you needed.

Watch for intensification. Healthy venting gradually reduces emotional charge; unhealthy venting increases it. If you feel angrier, more hopeless, or more convinced of catastrophe after talking than before, something is going wrong. The point of talking about feelings is to digest them, not marinate in them.

How to Vent Productively

The goal isn’t to stop talking about difficult things. Connection and emotional support are fundamental human needs. The goal is to shift how you talk so that the conversation serves its purpose: helping you process, not just express.

Start with a time limit. Tell your friend you need fifteen minutes to vent, and then you want their honest perspective. The boundary prevents spiraling and signals that you’re looking for something beyond just being heard. Open-ended venting sessions tend to drift into co-rumination; bounded ones stay more focused.

Ask for what you actually need. Sometimes you need validation; sometimes you need advice; sometimes you need someone to tell you you’re overreacting. Clarifying this upfront helps your listener respond in ways that actually help. “I just need you to tell me I’m not crazy” is a different conversation than “I need help figuring out what to do.”

Build in the pivot. After you’ve expressed the feelings, deliberately shift toward analysis or action. What do you think is really going on here? What’s your part in this? What options do you have? This pivot moves the conversation from venting to processing. It doesn’t mean skipping the emotional expression; it means not stopping there.

Write before you talk. Pennebaker’s research shows that writing about difficult experiences, even for just fifteen minutes, helps people organize their thoughts and begin the sense-making process. Jotting down what you want to say before calling a friend can help you identify what’s actually bothering you and prevent the conversation from becoming a formless complaint session.

Being a Better Listener for Others

Understanding these dynamics also helps when you’re on the receiving end of someone else’s venting. You can offer more than passive agreement.

The most helpful listeners don’t just validate; they gently prompt reflection. Questions like “What do you think is underneath that?” or “Have you noticed a pattern here?” can help the speaker move from venting to processing without feeling dismissed or lectured.

Resist the urge to match frustration with frustration. When a friend is angry, it’s tempting to amp up your own outrage on their behalf. This feels supportive but often just intensifies their emotional state. Calm, curious listening tends to help more than enthusiastic co-rumination, even if it feels less immediately satisfying.

Sometimes the most caring thing you can do is suggest a limit. “That sounds really hard. Do you want to talk about it for a few more minutes and then do something fun together?” This isn’t dismissive; it’s recognizing that endless processing has diminishing returns and that changing contexts can be its own form of relief.

Venting is a tool, and like any tool, its value depends on how you use it. Talking about problems with people who care about us is one of the best resources we have for managing life’s difficulties. But talking itself isn’t the cure. The cure is the processing that can happen through talking, the making sense, the gaining perspective, the gradual loosening of what felt impossibly tight. That’s the kind of conversation worth having.