In June 2025, the World Health Organization released findings that should have made front-page news everywhere: loneliness is now linked to an estimated 871,000 deaths annually, roughly 100 deaths every hour worldwide. One in six people globally reports experiencing loneliness, with the highest rates among adolescents and young adults. The health risks of chronic disconnection rival those of smoking 15 cigarettes a day.

These aren’t abstract statistics. They describe something many of us recognize in our own lives or the lives of people we love. The friend who seems fine on social media but admits to feeling profoundly alone. The parent who moved for work and never quite rebuilt their social world. The colleague who fills every evening with streaming shows because the silence of an empty apartment feels unbearable.

The loneliness epidemic is real, well-documented, and increasingly urgent. But the research also offers something beyond alarm: a growing understanding of what actually helps, what doesn’t, and why connection matters so much more than we might have assumed.

The Scope of the Crisis

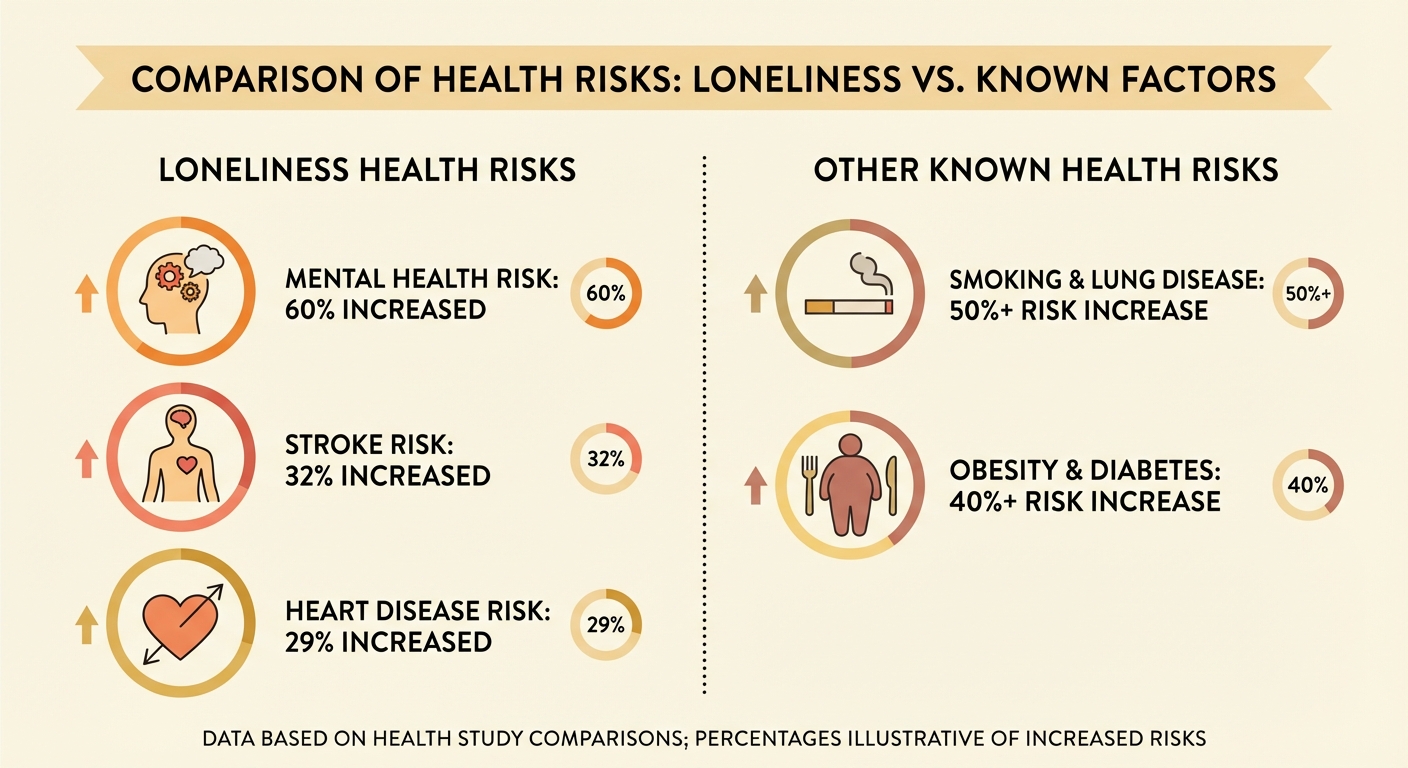

The WHO Commission on Social Connection brought together researchers from around the world to assess the state of human connection. Their findings paint a sobering picture. Social isolation and loneliness increase the risk of stroke by 32%, heart disease by 29%, and dementia by 50%. The effects on mental health are even more pronounced: lacking social connection increases the risk of depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders by as much as 60%.

In the United States, the pattern is particularly striking among middle-aged adults. AARP’s 2025 study found that 40% of adults age 45 and older report feeling lonely, a significant increase from 35% in previous surveys. Adults in their 40s and 50s face unique pressures: work stress, caregiving responsibilities for both children and aging parents, and changing family dynamics that can leave them feeling isolated even when surrounded by obligations.

Perhaps most surprising is the shift in gender patterns. Men now report higher rates of loneliness than women, 42% compared to 37%, reversing the gender parity seen in earlier studies. This may reflect changing social structures that have eroded traditional sources of male connection, from declining participation in community organizations to the weakening of workplace relationships in an era of remote work and job instability.

Why Connection Matters So Much

The biological case for social connection is now well-established. Humans evolved as social creatures, and our nervous systems are literally wired for connection. Positive social interactions trigger the release of oxytocin, sometimes called the “bonding hormone,” which reduces stress and promotes feelings of trust and safety. Regular social contact helps regulate cortisol levels, reducing chronic inflammation that contributes to numerous diseases.

But the research reveals something deeper than just stress reduction. According to findings published in PMC, social connection can protect health across the entire lifespan, fostering mental health, reducing inflammation, lowering the risk of serious health problems, and preventing early death. The mechanisms are multiple and interconnected: social support buffers against stress, meaningful relationships provide purpose and meaning, and regular interaction keeps cognitive systems engaged and functioning.

The flip side is equally important to understand. When we lack connection, our bodies respond as if we’re under threat. The stress response system stays activated, inflammation increases, and the immune system becomes compromised. This isn’t weakness or personal failing; it’s biology. We are designed for connection, and when that need goes unmet, our health suffers in measurable, predictable ways.

The Young Adult Crisis

While loneliness affects every age group, adolescents and young adults face unprecedented challenges. Research from Harvard found that 61% of young people report “serious loneliness,” as do over half of mothers with small children. On college campuses, nearly half of all students screen positive for loneliness according to National College Health Assessment data.

Several factors converge to create this perfect storm. The transition from structured environments like high school to more autonomous settings like college or early career requires building new social networks from scratch, a skill many young people haven’t developed. Social media creates the illusion of connection while often failing to provide the depth of interaction that actually reduces loneliness. Economic pressures force young adults to delay traditional markers of connection, like forming families or putting down roots in communities.

The University of Iowa’s Scanlan Center for School Mental Health emphasizes that even brief positive interactions, what researchers call “micro-moments of connection,” can make a significant difference. These aren’t the deep friendships we often assume are necessary; they’re the small exchanges that create what psychologist Barbara Fredrickson calls “positivity resonance,” the shared experience of positive emotion that builds over time.

What Actually Helps (And What Doesn’t)

The research is increasingly clear about what interventions actually reduce loneliness. According to a comprehensive review in PMC, solutions exist at multiple levels: national policies, community infrastructure, and individual psychological interventions. But not all approaches are equally effective.

Simply increasing the quantity of social contact doesn’t necessarily help. You can feel profoundly lonely at a crowded party or in a marriage where emotional connection has eroded. What matters is the quality of connection, whether interactions feel meaningful, whether you feel seen and understood, whether there’s genuine reciprocity.

Addressing the cognitive patterns that perpetuate loneliness often proves more effective than just trying to meet more people. Lonely individuals tend to perceive social situations more negatively, expect rejection, and withdraw from opportunities for connection. Interventions that help people challenge these patterns, like cognitive behavioral approaches, show stronger results than those focused solely on social skills training or increasing social opportunities.

That said, structural factors matter enormously. Communities with robust social infrastructure, including parks, libraries, community centers, and walkable neighborhoods that encourage spontaneous interaction, have lower rates of loneliness. The decline of these “third places,” spaces that are neither home nor work where people can gather informally, correlates with rising disconnection.

The Social Media Question

Given how much time people spend on social media, researchers have paid close attention to its relationship with loneliness. The findings may surprise those who assume social media is primarily to blame for the epidemic.

A comprehensive review published in the Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences found that social media use is only weakly related to loneliness and explains little variance in loneliness compared to other factors. There’s no evidence it causes loneliness. On any given day, social media may be used to promote belongingness, but it doesn’t appear to be an effective way to cope with loneliness in the long term.

This nuanced finding suggests that social media is neither the villain it’s often portrayed as nor a substitute for genuine connection. It can supplement relationships, helping maintain contact with distant friends and family, but it can’t replace the embodied, reciprocal interactions that our nervous systems actually need.

Building Connection in Your Own Life

The research points toward several evidence-based strategies for reducing loneliness. These aren’t quick fixes, but they align with what we know about how connection actually works.

Prioritize quality over quantity. You don’t need dozens of friends. Research consistently shows that having even a few relationships characterized by genuine understanding and reciprocity protects against loneliness. Focus on deepening existing connections rather than constantly seeking new ones.

Embrace micro-moments. The barista you see every morning, the neighbor you wave to, the colleague you chat with in the elevator, these brief interactions matter more than you might think. They build what researchers call “weak ties,” which contribute to a sense of belonging and community even when they don’t involve deep intimacy.

Challenge negative interpretations. If you tend to assume people don’t want to connect with you or that you’ll be rejected, notice these thoughts and question them. Research on loneliness interventions shows that addressing maladaptive social cognition is often more effective than social skills training.

Create structure for connection. In the absence of the automatic social structures that previous generations enjoyed, like neighborhood organizations or regular religious attendance, many people need to be more intentional. Joining a class, a club, or a regular group activity provides recurring opportunities for connection to develop naturally over time.

Be a connector yourself. Reaching out to others not only builds your own relationships but contributes to the social fabric that benefits everyone. Send the text. Make the call. Invite someone for coffee. These small acts of initiative are how relationships begin and deepen.

Your Invitation

The loneliness epidemic is a public health crisis, but it’s also an invitation. Every interaction you have, every moment of genuine presence you offer another person, is a small act of repair in a disconnected world.

You can’t solve this alone, and you’re not meant to. Connection is, by definition, something that happens between people. But you can contribute to the solution by being someone who reaches out, who shows up, who takes the small risks that genuine connection requires.

The research is clear that we’re often kinder to each other than we expect. The person you’re hesitant to text might be waiting for someone to reach out. The neighbor you’ve never spoken to might be lonelier than you imagine. The friend you’ve lost touch with might be hoping someone remembers them.

You don’t need to be someone’s best friend to matter to them. Sometimes the most meaningful connections are the small ones, the brief interactions that remind us we’re seen, that we belong, that we’re part of something larger than ourselves. In a world where holding space for each other has become increasingly rare, even small gestures of connection can be profound.

The loneliness epidemic is real. But so is the human capacity for connection, for reaching across the distance that separates us, for building the relationships and communities that help us thrive. That capacity lives in you, in all of us. The question is what we choose to do with it.

Sources: WHO Commission on Social Connection, AARP 2025 Loneliness Study, PMC on social connection and health, Psychology Today, University of Iowa Scanlan Center, PMC on loneliness interventions, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, Barbara Fredrickson on positivity resonance.