Your to-do list has 47 items. You added 12 today. You completed maybe 4. The list grows faster than you can check things off, and you feel perpetually behind despite working constantly.

Here’s what nobody tells you about productivity: the problem isn’t that you’re not doing enough. It’s that you’re trying to do everything.

Every yes to something unimportant becomes a no to something that matters. Every commitment to the trivial crowds out the essential. Your capacity is finite, but your to-do list pretends otherwise.

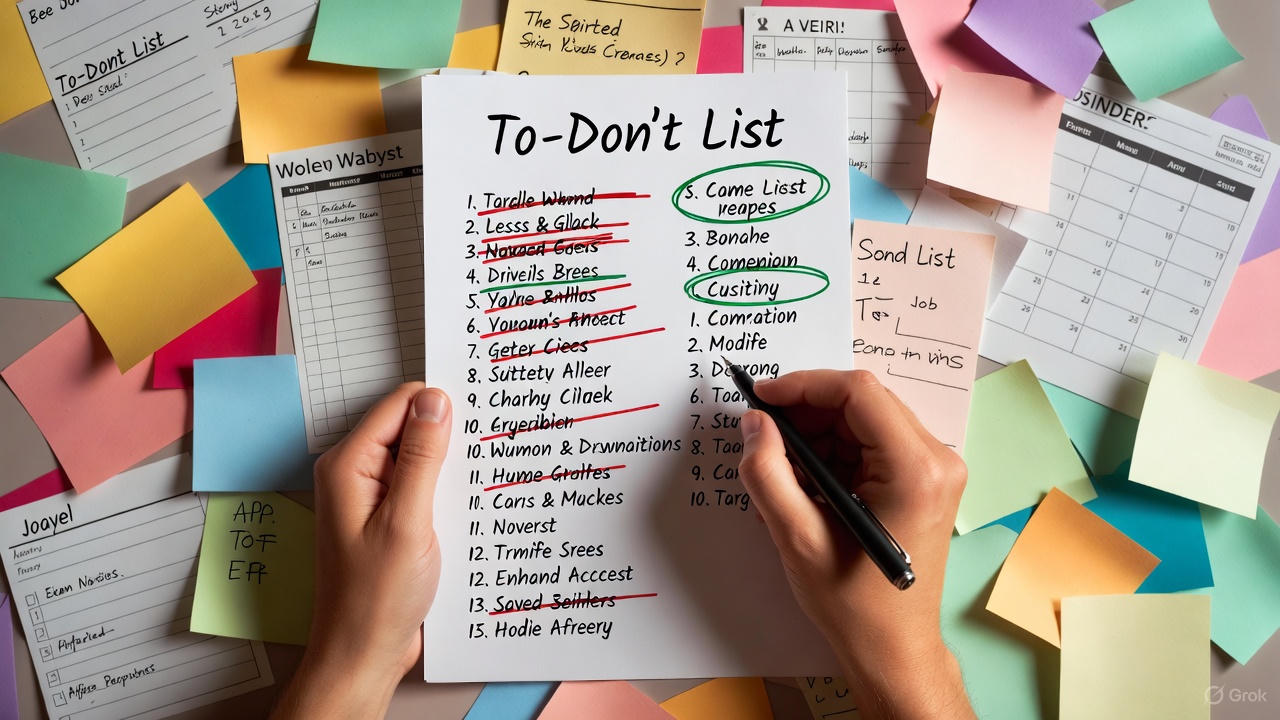

The solution isn’t a better system for managing more. It’s a deliberate inventory of what you’re intentionally not doing. A to-don’t list.

The Selectivity Paradox

Warren Buffett’s famous observation cuts to the heart of the issue: “The difference between successful people and really successful people is that really successful people say no to almost everything.” That’s not about working less. It’s about being viciously selective about what receives your limited attention.

The Pareto principle suggests that roughly 80% of results come from 20% of efforts. Applied honestly to your life, this means you could eliminate most of what you’re doing and lose only a fraction of actual value, while freeing up enormous time and energy for what genuinely matters.

The to-don’t list makes this elimination concrete. It’s where you write down the meetings you’re declining, the requests you’re refusing, the activities you’re releasing. Not because they’re bad, but because they’re not the best use of your finite resources.

Identify Your Time Thieves

Creating your to-don’t list requires honest assessment of where your hours actually go. Cal Newport’s research on deep work reveals that most knowledge workers spend shockingly little time on their most important tasks, while hours disappear into email, meetings, and digital distraction.

Start with a time audit. Track one week in detail: what you do each hour, which activities energize versus drain you, what you accomplish versus what feels busy but produces nothing. Patterns emerge quickly. Maybe you’re spending eight hours weekly in meetings that contribute nothing. Maybe social media consumes five hours you thought was thirty minutes. Maybe you’re over-preparing for things that don’t require perfection.

The audit reveals where waste lives. The to-don’t list eliminates it: “I will not attend meetings without clear agendas. I will not check email more than three times daily. I will not scroll social media during work hours.”

Beyond time, some activities drain energy disproportionate to their duration. A thirty-minute conversation with the wrong person can deplete you for hours. Work you hate sucks energy beyond its clock time. Obligations you carry only from guilt or social pressure weigh more than their calendar footprint suggests.

Put these on your to-don’t list not because they take lots of time, but because they take disproportionate energy.

The Art of Saying No

The to-don’t list only works if you actually decline things. That requires getting comfortable with a complete sentence: “No.”

You don’t owe lengthy explanations. When someone asks for your time, “I appreciate you thinking of me, but I’m not able to take that on right now” is sufficient. For invitations: “Thanks for including me, but I need to decline.” For people who push: “I understand it’s important to you. My answer is still no.”

If you struggle with setting boundaries without guilt, remember this: the discomfort of saying no is temporary. The relief of having time for what actually matters is permanent. Every boundary you hold is a choice about what kind of life you’re building.

Greg McKeown, author of “Essentialism,” frames it this way: if it’s not a clear yes, it’s a no. The activities and commitments that deserve your time should be obvious, not negotiable. Everything else belongs on the to-don’t list.

Permission to Quit What Isn’t Working

The to-don’t list includes things you’ve already started but need to stop. Projects you’re 60% through but no longer care about. Roles you said yes to months ago that now drain rather than energize. Habits and routines that made sense once but don’t serve the person you’re becoming.

Sunk cost fallacy tells us to finish what we started because we already invested time. But past investment doesn’t justify future waste. You’re allowed to quit things that no longer serve you, even when quitting feels like failure.

Your to-don’t list evolves as your life evolves. Review it weekly for tactical items: which specific meetings to skip, which requests to decline. Review monthly for patterns: what obligations can you release entirely? Review quarterly for bigger decisions: what projects should you abandon, what roles should you resign from?

Your Invitation

This week, create your first to-don’t list. Write down three to five things you’re going to stop doing. Be specific: not “spend less time on email” but “I will not check email before 10 AM or after 6 PM.”

Then honor what you wrote. When those activities try to creep back in, and they will, refer to your list and decline.

Notice what happens in the space you create. Notice what becomes possible when you’re not filling every hour with obligation. The to-don’t list won’t make you superhuman, but it might make you sane.

In a world that demands everything from everyone, selective refusal is a radical act. Say no to the many so you can say yes to the few that matter. That’s not limitation. That’s liberation.

Sources: Warren Buffett, Cal Newport’s research on deep work, Greg McKeown’s “Essentialism.”.