It’s 6 PM and you’re staring into the refrigerator, unable to decide what to eat. The contents haven’t changed since this morning. You have at least four reasonable options. But something in your brain has simply stopped working, and choosing between chicken and pasta feels like being asked to solve differential equations. You close the door, grab crackers, and wonder why you can’t seem to function like an adult.

The problem isn’t the dinner decision. It’s the 347 decisions you made before it. What to wear, how to respond to that email, which tasks to prioritize, whether to attend the meeting, how to phrase the difficult message, where to eat lunch, when to take a break. Each choice, however small, drew from the same limited pool of mental energy. By evening, that pool is drained, and even trivial decisions feel impossible.

The Science of Depleted Will

Decision fatigue isn’t metaphor; it’s measurable physiology. Studies in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology found that people who made a series of choices showed reduced self-control and willpower on subsequent tasks. Their blood glucose dropped. Their ability to persist through challenges diminished. The act of deciding, even about things that seem insignificant, consumes real cognitive resources.

The most famous demonstration of this comes from research on Israeli parole boards. Judges reviewing prisoner cases were significantly more likely to grant parole at the beginning of the day and right after food breaks. As the day progressed and decisions accumulated, they increasingly defaulted to the safer choice, which in this context meant denying parole. Their judgments weren’t becoming more accurate; they were becoming more conservative as their decision-making capacity depleted.

Your brain treats decisions as work. Whether you’re choosing a life partner or choosing a sandwich, the process requires evaluating options, predicting outcomes, and committing to a course of action. This is cognitively expensive. Evolution didn’t prepare us for a world where we’d face dozens of choices before breakfast, hundreds before dinner, and be expected to make good ones throughout.

The modern environment amplifies this problem relentlessly. Previous generations had fewer options and more defaults. You wore what you had, ate what was available, worked at the job nearby. The paralysis of infinite choice is historically novel. Your great-grandparents never faced decision fatigue from scrolling through 400 streaming options; they watched whatever was on the three channels or read a book.

Where Your Choices Are Hiding

Before you can reduce decision fatigue, you need to see where your decisions are actually going. Most of us dramatically underestimate how many choices we make daily because so many of them fly under conscious radar. A quick audit usually reveals surprising patterns.

Morning routines are dense with hidden decisions. What time to wake up (snooze or not?), what to wear, what to eat, which route to take, whether to exercise, what to listen to during the commute, how to respond to the messages that arrived overnight. Each micro-choice chips away at your capacity before you’ve started your “real” work.

Work itself compounds the problem. Email alone can generate dozens of decisions per hour: respond now or later, how to phrase things, who to CC, whether this requires a meeting, how to prioritize against other tasks. Open-plan offices and always-on communication tools create constant interruption, and each interruption requires a decision about whether and how to engage.

Consumer environments are specifically designed to maximize your choices. A typical grocery store contains 40,000+ products. Online shopping offers infinite options with one-click access. Even entertainment, which should be restorative, has become a decision gauntlet. The average American spends 7 minutes deciding what to watch on streaming services, often choosing nothing or defaulting to something they’ve already seen.

Relationships and social obligations add another layer. Should you attend this event? How should you respond to that invitation? Is it okay to cancel? What gift should you bring? The emotional weight of interpersonal decisions often exceeds their apparent significance, draining energy disproportionate to their importance.

The Power of Predetermined Choices

The most effective antidote to decision fatigue is eliminating decisions entirely through systems, routines, and pre-commitments. This isn’t about becoming rigid; it’s about being strategic about which choices deserve your mental energy and which don’t.

Steve Jobs famously wore the same outfit daily. Mark Zuckerberg does too. This isn’t eccentric affectation; it’s resource management. By eliminating the clothing decision, they preserved mental energy for choices that actually mattered to their work. You don’t need to adopt a uniform, but identifying your version of this principle can be transformative.

Meal planning works on the same principle. Deciding on Sunday what you’ll eat all week means you only make the decision once, not fourteen times. Subscription services for regular purchases, automatic bill pay, and scheduled recurring commitments all remove decisions from your daily load. The goal is to let past-you make choices that present-you doesn’t have to revisit.

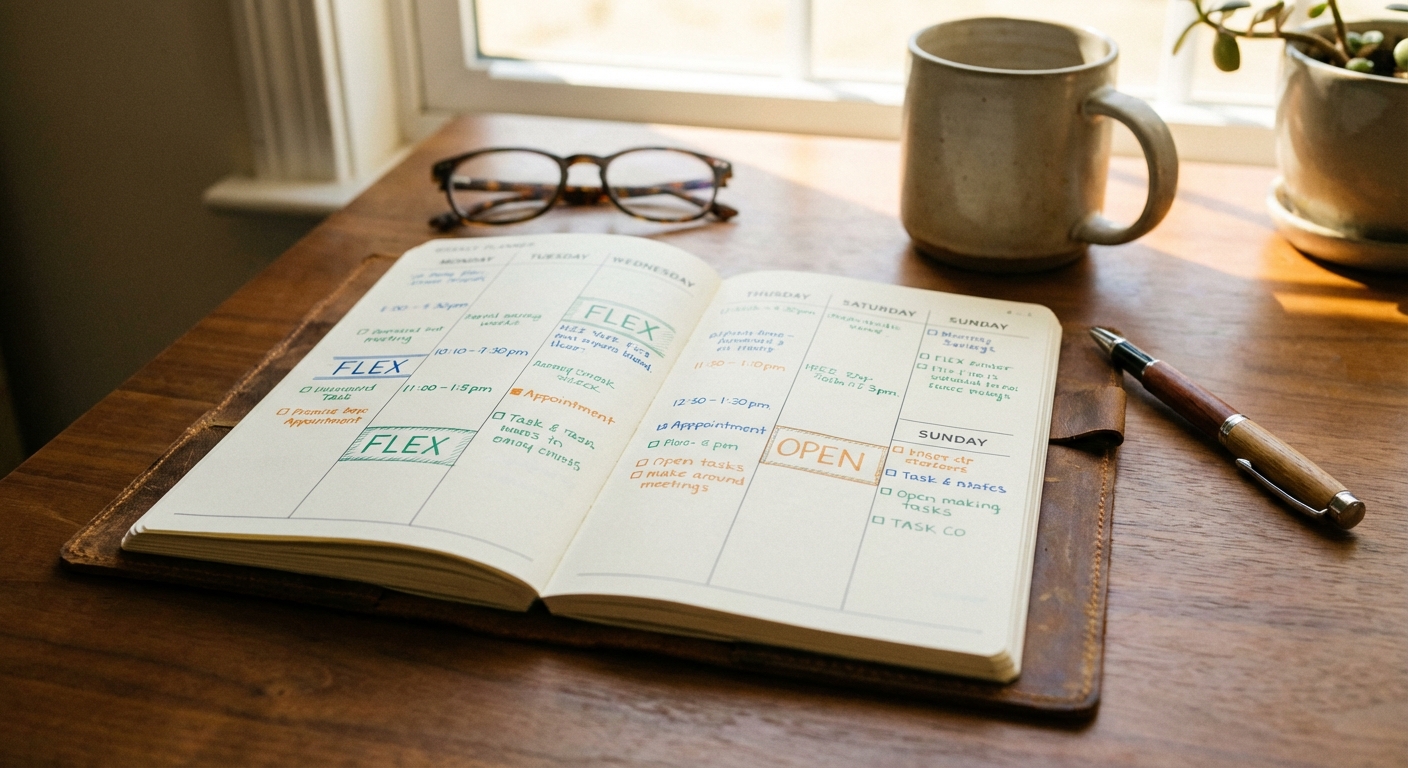

Time blocking, explored extensively in deep work research, applies this to your schedule. Instead of deciding moment-to-moment what to work on, you decide once per week or day, then simply follow the plan. The decision about what to do at 10 AM was already made; now you just execute. This preserves cognitive resources for the actual work rather than the meta-work of deciding what to work on.

Default settings matter more than we realize. When employers make retirement savings opt-out instead of opt-in, participation skyrockets. When you make healthy food the easiest option and junk food hard to access, you eat better. Designing your environment to have good defaults means the path of least resistance leads somewhere you want to go.

Protecting Your Peak Hours

Decision-making quality varies throughout the day, and aligning your choice load with your cognitive capacity can significantly improve outcomes. Most people have higher willpower and better judgment in the morning, before the day’s decisions have accumulated. This suggests a simple strategy: make important decisions early.

Schedule significant choices for your peak hours. Performance reviews, strategic planning, financial decisions, difficult conversations, these all deserve your fresh cognitive resources. Pushing them to late afternoon because your calendar looks full in the morning is a false economy; you’ll either make worse decisions or burn more energy making adequate ones.

Batch similar decisions together. Rather than responding to emails throughout the day, creating dozens of micro-decisions, handle them in defined blocks. Rather than deciding each meal separately, plan the week’s food at once. Rather than evaluating each invitation individually, set policies about what kinds of events you attend. Batching reduces the cognitive overhead of context-switching and lets you build momentum within a decision category.

Create bright-line rules that eliminate entire categories of decisions. “I don’t check email before 9 AM” removes the daily choice about morning email. “I always take the stairs below five floors” removes fitness micro-decisions. “I don’t accept meetings on Wednesday mornings” protects that time without requiring evaluation each time. These rules feel restrictive initially but become liberating as the decisions they eliminate stop draining you.

Rest strategically between decision-heavy periods. The Israeli parole study showed judges improved after food breaks, and glucose appears to play a role in willpower restoration. But mental downtime matters too. Switching to a non-demanding activity, taking a walk, or even doing nothing for a few minutes can partially restore decision-making capacity.

The Art of Good Enough

Perfectionism and decision fatigue feed each other. The drive to make the optimal choice in every situation dramatically increases the cognitive cost of each decision. You research extensively, compare obsessively, and second-guess constantly, all while the decision drains more energy than it would if you accepted a satisfactory outcome.

Psychologist Barry Schwartz distinguishes between “maximizers” who seek the best possible option and “satisficers” who seek an option that meets their criteria. Research consistently shows satisficers are happier with their choices and experience less regret, even when maximizers technically choose better options. The psychological cost of maximizing usually exceeds the marginal benefit of the slightly better outcome.

For most decisions, “good enough” is good enough. The restaurant you choose doesn’t need to be the best restaurant; it needs to be a place you’ll enjoy. The pants you buy don’t need to be the optimal pants; they need to fit and look decent. The more decisions you can downgrade from “find the best” to “find something acceptable,” the more mental energy you conserve for choices that genuinely matter.

Setting decision time limits can force satisficing when your tendency is to maximize. Give yourself 30 seconds to choose a lunch spot, 5 minutes to pick a movie, 15 minutes to draft an email response. The artificial constraint prevents overthinking and builds the muscle of trusting your quick judgment. Most decisions genuinely aren’t worth more time than this.

Designing for Tomorrow

The best time to make decisions is when you’re not under pressure to execute them. This is why Sunday resets work so well: you decide things on Sunday that you simply do throughout the week. The decision and the action are separated, allowing each to happen at optimal moments.

Evening planning for the next day is a specific application of this principle. Before you stop working, decide what you’ll work on first tomorrow. This accomplishes two things: it prevents the morning decision about where to start, and it lets your subconscious process the upcoming work overnight. You’ll often wake up with clarity or ideas that wouldn’t have emerged if you’d made the decision cold.

Systems thinking matters here. Rather than making the same decision repeatedly, ask whether you can create a system or rule that handles it automatically. If you regularly decide whether to attend certain types of meetings, create a policy. If you frequently choose between similar options, create criteria. If you repeatedly wonder what to do in a situation, create a default response. Each system removes a recurring decision from your daily load.

The ultimate goal isn’t to eliminate all decisions; it’s to spend your decision-making capacity on choices that matter. Some decisions deserve careful thought and abundant mental energy. Most don’t. Learning to tell the difference, and designing your life accordingly, is one of the highest-leverage changes you can make.

Your Invitation

Look at tomorrow’s schedule and identify the decisions hiding inside it. Not the big obvious ones, but the small choices you’ll face throughout the day. What can you decide tonight instead? What can you eliminate entirely through a rule or default? What can you batch together rather than spreading through the day?

You don’t need to transform everything at once. Pick one recurring decision that drains you, something you face daily or weekly that feels harder than it should. Create a system, rule, or pre-commitment that removes it from your active decision load. Notice how it feels to simply do rather than decide.

The goal isn’t robotic efficiency. It’s protecting the creative, thoughtful, strategic part of you that gets buried under an avalanche of trivial choices. That part has important things to contribute. It just needs the energy to do so.

Your decisions shape your life. Make sure you have the capacity to make the ones that matter.

Sources: Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Israeli parole board study (Danziger, Levav, Avnaim-Pesso), The Paradox of Choice (Barry Schwartz).