December arrives and with it, the annual pressure to optimize. New year, new habits, new systems, new you. The productivity industry gears up to sell you planners, apps, and courses promising to help you do more, achieve more, become more.

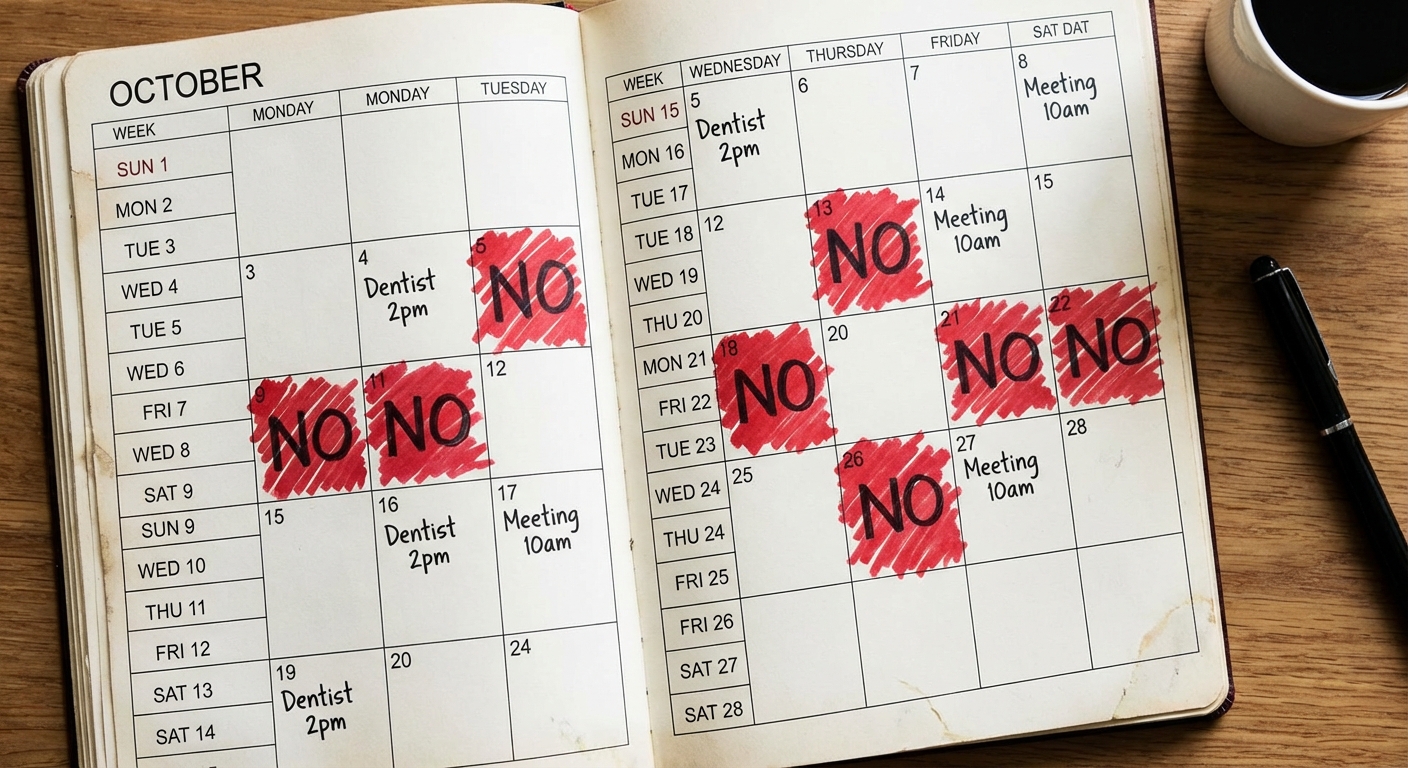

Before you add anything else to your overflowing plate, consider a radical alternative: subtraction.

The most productive people you admire aren’t productive because they’ve mastered the art of cramming more into each day. They’ve mastered the art of not doing things. The commitments they’ve declined, the meetings they’ve opted out of, the busywork they’ve learned to ignore, that’s where their capacity comes from.

The Addition Trap

Every productivity system promises the same thing: do this new thing and you’ll be more effective. Install this app. Try this morning routine. Adopt this framework. And some of these tools genuinely help. But there’s a problem nobody mentions: implementing a new system takes energy, attention, and time, exactly the resources you’re trying to create.

This is why most productivity interventions fail. You’re already exhausted and overwhelmed. Adding something new, even something designed to help, increases your burden in the short term. Most people abandon the new system before experiencing its benefits, not because the system was bad, but because they didn’t have the capacity to adopt it.

Dr. Gloria Mark’s research at UC Irvine on attention and productivity found that the average knowledge worker switches tasks every three minutes. Each switch carries a cognitive cost. We’re not struggling because we lack good systems; we’re struggling because we’re doing too much, and no system can compensate for fundamental overcommitment.

The real productivity opportunity isn’t finding a better way to manage your tasks. It’s having fewer tasks to manage.

Building Your Stop-Doing List

Warren Buffett famously advises making a list of your top 25 goals, circling the top 5, and treating the other 20 as your “avoid at all costs” list. The logic is counterintuitive but sound: the things that prevent you from achieving your real priorities aren’t obviously wasteful activities. They’re second-tier good ideas that consume attention that should go to first-tier essentials.

Your stop-doing list isn’t about eliminating the clearly unproductive, though that helps too. It’s about getting ruthlessly honest about which of your current commitments actually serve your goals and which are just comfortable habits, legacy obligations, or things you said yes to before you knew better. If this sounds familiar, you might also benefit from creating a to-don’t list that makes your strategic eliminations explicit.

Try this exercise. Write down everything you did last week that took more than 30 minutes. Then for each item, ask two questions. First: if I had never started doing this, would I start now? Second: what would actually happen if I stopped? You’ll find that many activities fail both tests. You do them because you’ve always done them, and if you stopped, the consequences would be minor or nonexistent.

The hardest stop-doing decisions aren’t about bad activities. They’re about good activities that aren’t your best activities. That book club you enjoy but never quite prioritize. That volunteer committee that matters to you but leaves you depleted. That side project that excites you but fragments your focus. Being busy with good things is still being busy.

The Five Categories of Productive Elimination

Not everything is equally worth stopping. Some eliminations create massive capacity; others barely register. Here’s where to look for high-impact subtractions.

Zombie commitments are things you agreed to in the past that no longer serve you but keep shambling forward through inertia. That weekly check-in call that stopped being useful six months ago. That subscription you keep paying for but never use. That volunteer role you took on when you had more bandwidth. These are often the easiest to stop because nobody is really depending on them anymore, but guilt keeps them alive.

Performance activities are things you do to appear productive rather than to be productive. Excessive email checking. Attending meetings you don’t contribute to or learn from. Organizing and reorganizing your task system. Creating elaborate plans you don’t execute. These feel like work but produce little value.

Other people’s priorities are requests that serve someone else’s goals while draining your capacity for your own. Not every request deserves a yes. Not every fire is yours to fight. Learning to say no, or to say “not now,” or to say “here’s what I can offer instead,” is a productivity skill that no app can replace.

Energy vampires are activities that leave you depleted out of proportion to their apparent cost. A one-hour meeting that somehow ruins your whole afternoon. An email thread that hijacks your attention for days. A relationship that takes more than it gives. These are often hard to quantify but easy to feel. Learning to manage your energy rather than just your time can help you identify which activities cost more than they’re worth.

Good-enough perfectionism is the time spent taking something from 90% to 95% when 90% would have been perfectly adequate. This is expensive because it’s invisible: you never see the other things you could have done with that time. The standard for most things should be “good enough,” with excellence reserved for what truly matters.

The Art of the Graceful Exit

Knowing what to stop is only half the challenge. The other half is actually stopping without damaging relationships or creating more problems than you solve. Most of us keep doing things we should quit because we don’t know how to exit gracefully.

For ongoing commitments, the key is advance notice and transition support. “I’ve realized I need to step back from this role, and I want to make sure I leave you in a good position. I can stay for another month while we find a replacement, and I’m happy to help train them.” This is infinitely better than either abrupt abandonment or quiet resentment.

For individual requests, practice the “positive no”: acknowledge the request, decline clearly, and offer what you can. “I can’t take on that project, but here’s a resource that might help” or “That’s not possible this month; can we revisit in the new year?” You’re not required to explain or justify. A simple “that doesn’t work for me” is a complete sentence.

The hardest exits are from your own expectations. That goal you’ve been pursuing that no longer fits who you’ve become. That identity you’ve been maintaining that costs more than it’s worth. These aren’t things you can politely decline; they’re things you have to grieve. But grief is sometimes the price of growth. Making peace with letting go of goals that no longer serve you is a skill worth developing.

What Remains

There’s a specific kind of clarity that emerges when you stop doing things. At first it feels like emptiness, a discomfort that years of busyness have trained you to avoid. But as you sit with that space, it transforms into something else: room to think, room to notice, room to do the things that actually matter with the attention they deserve.

Cal Newport’s concept of “deep work” requires this kind of space. You can’t do focused, meaningful work while juggling a dozen shallow commitments. The deep work becomes possible precisely because of what you’ve stopped doing. Subtraction creates the conditions for quality.

This doesn’t mean doing less forever. It means being intentional about what you add and when. It means creating capacity before making commitments rather than overcommitting and hoping you’ll somehow find time. It means treating your attention as the finite resource it is, rather than pretending you can always fit one more thing.

Your Invitation

Before you plan what to add in the coming year, take inventory of what to subtract.

Make your stop-doing list. Be honest about which commitments drain you without delivering proportionate value. Identify the zombie activities that persist only through inertia. Notice the performance behaviors that feel productive but aren’t.

Then, one by one, begin to exit. Give proper notice. Transition gracefully. Grieve if necessary. And notice what emerges in the space you create.

Productivity isn’t about doing more. It’s about doing what matters. And the first step toward doing what matters is stopping what doesn’t.

Sources: Dr. Gloria Mark’s research on attention and productivity at UC Irvine, Warren Buffett’s prioritization framework, Cal Newport’s deep work research.