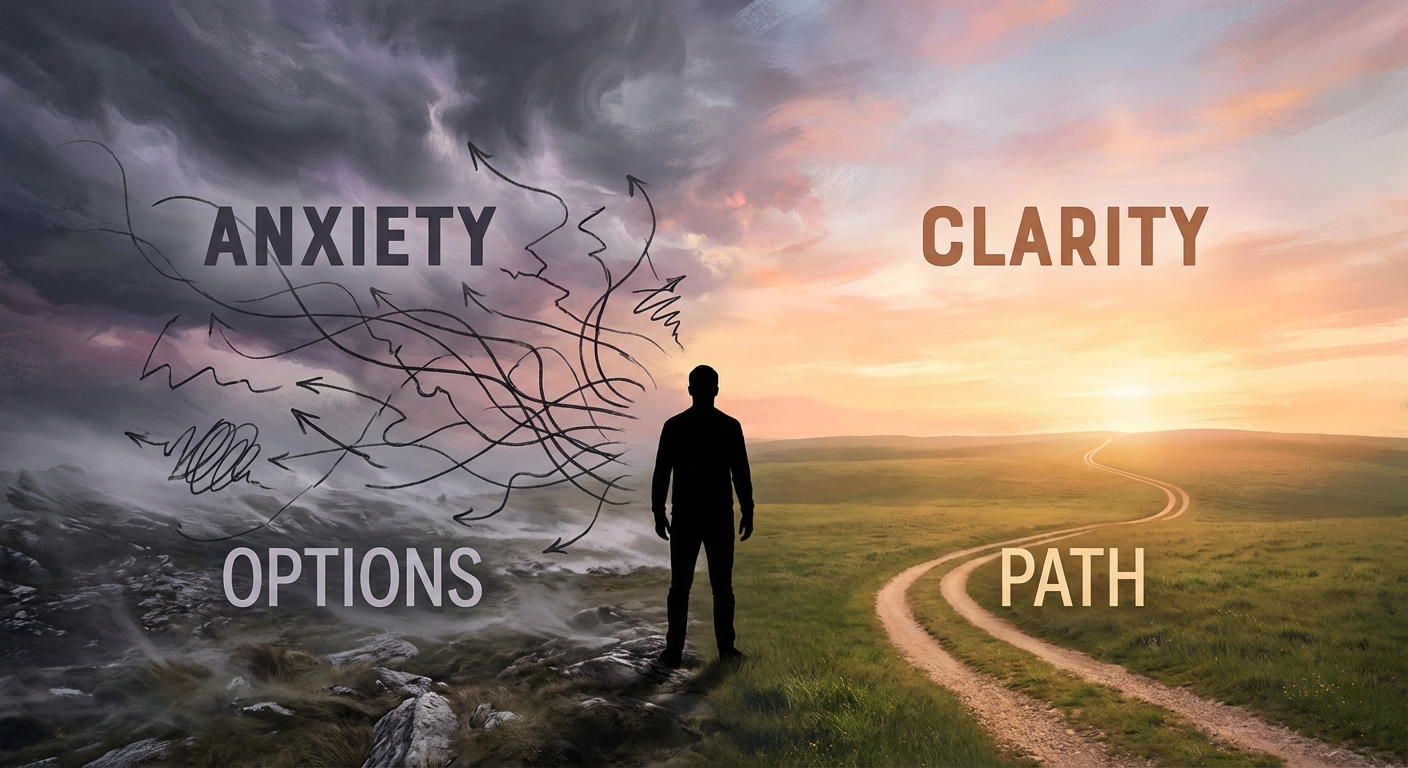

You’re standing in the cereal aisle, paralyzed. There are 47 options. You’ve been here for eight minutes. You pick up a box, read the nutrition label, put it back. Pick up another. Compare. Put it back. Meanwhile, a voice in your head insists that the perfect cereal exists, and if you just look a little longer, you’ll find it.

This scene plays out across every domain of modern life. The restaurant menu with 200 items. The dating app with unlimited profiles. The career paths that multiply faster than you can research them. We’ve been sold a story that more options equal more freedom, and more freedom equals more happiness. The research tells a different story entirely.

Psychologist Barry Schwartz has spent decades studying what happens when choice becomes overwhelming. His findings are counterintuitive but consistent: the people who insist on finding the best possible option are measurably less happy than those who settle for something that’s merely good enough. The maximizers, as Schwartz calls them, are more likely to be depressed, more likely to regret their decisions, and less satisfied with outcomes that are objectively equal to or better than what the “settlers” chose.

The Paradox Nobody Warned You About

The problem isn’t choice itself. Having options is genuinely valuable, and the ability to shape your own life matters deeply. The problem is what happens in our minds when options multiply beyond a certain threshold. Schwartz’s research, detailed in his influential book The Paradox of Choice, found that people faced with 24 jam options at a grocery display were one-tenth as likely to buy anything compared to people offered just six options. More choices didn’t create more action. They created paralysis.

This phenomenon has been replicated across contexts ranging from retirement savings to online dating. A 2024 study published in the International Journal of Social Science and Economic Research examined choice overload in online food delivery apps and found a significant relationship between excessive options and decision paralysis, with people under 40 particularly affected. The platforms designed to give us everything we want may be undermining our ability to choose anything at all.

The psychological mechanics are revealing. When you’re trying to maximize, to find the objectively best option, every choice becomes an exhaustive research project. You’re not just picking something. You’re defending that pick against every alternative you didn’t choose. The opportunity cost feels infinite because you’re imagining all the paths not taken. Even when you finally decide, a part of your brain keeps running the comparison, wondering if you made a mistake.

Satisficers: The Unexpected Winners

Satisficers approach decisions differently. They have standards, criteria that matter to them, but once an option meets those standards, they stop looking. They don’t need the best apartment; they need an apartment that’s affordable, in the right neighborhood, with enough space. When they find one that checks those boxes, they sign the lease. They don’t spend another three weekends wondering if something better might appear.

This sounds like settling in the pejorative sense, but the research suggests it’s actually a form of wisdom. Satisficers consistently report higher life satisfaction, lower stress, and less regret than maximizers, even when their objective outcomes are similar or worse. They’re not less successful. They’re less tormented by their success.

The distinction isn’t about caring less. Satisficers can have high standards and pursue excellence in domains that matter to them. The difference is in their relationship to the process. They recognize that optimization has diminishing returns, that the difference between the “best” option and a “very good” option is usually marginal, and that the mental energy spent chasing perfection could be invested in actually living with the choice.

Dr. Schwartz found that maximizers tend to do objectively better on certain metrics, like starting salary after graduation, but they feel subjectively worse. The maximizer who negotiated $5,000 more than her satisficer classmate is more likely to wonder if she could have gotten $7,000. The satisficer who hit her target number moves on with her life.

Why Your Brain Keeps Searching

Understanding why maximizing feels so compelling, even when it backfires, helps explain why it’s so hard to stop. Several cognitive biases conspire to keep us searching long past the point of usefulness.

Regret aversion plays a central role. Research from The Decision Lab identifies how the fear of future regret, of choosing wrong and having to live with that choice, drives people to extend their search indefinitely. The irony is that this extended searching creates more opportunities for regret, not fewer. The more options you consider, the more alternatives you’ll imagine you should have chosen.

Loss aversion compounds the problem. Psychologists have established that losses feel roughly twice as painful as equivalent gains feel good. When you choose one option, you’re not just gaining that option; you’re losing every other option you could have chosen. For maximizers, every decision feels like multiple losses wrapped around a single gain. No wonder it’s exhausting.

There’s also a status element that’s hard to admit. In a culture that celebrates optimization, that fills podcasts and books with advice on getting the best deal, the best results, the best life, settling for good enough can feel like admitting defeat. The satisficer who says “this restaurant is fine, let’s eat here” might worry they’re revealing a lack of standards, a failure to live optimally. The research suggests they’re revealing something closer to emotional intelligence.

The Practice of Enough

Shifting from maximizing to satisficing isn’t about abandoning discernment. It’s about recalibrating where you invest your decision-making energy. Some choices genuinely warrant extensive research, such as major career moves, medical decisions, and significant financial commitments. Many choices don’t. The satisficer’s skill is knowing the difference.

Start by identifying your actual criteria before you begin searching. What are the three to five things that genuinely matter for this decision? Write them down. This prevents the common trap of discovering new criteria mid-search, which can extend the hunt indefinitely. If an apartment needs to be under $2,000, within 20 minutes of work, and have laundry in the building, those are your criteria. An apartment that meets all three is good enough, even if there might be a marginally better one you haven’t seen yet.

Practice recognizing when you’ve entered diminishing returns. The first 80% of value in any search typically comes from the first 20% of effort. The remaining 20% of value requires 80% more effort. Maximizers get stuck in that inefficient tail, convinced that just a little more research will reveal the perfect option. Satisficers recognize that their time and mental energy are finite resources with opportunity costs of their own.

Build tolerance for the discomfort of not knowing. When you choose something good enough and stop looking, there’s a brief moment of uncertainty. Did you miss something better? The answer is probably yes, statistically speaking. There’s almost always something marginally better somewhere. The satisficer’s insight is that this doesn’t matter. The costs of endless searching exceed the benefits of marginal improvement.

Relationships, Careers, and the Myth of the Perfect Fit

The maximizing mindset causes particular damage in domains where “better” is subjective and the search can be infinite. Dating apps have created the perfect laboratory for maximizing dysfunction. Research on choice in online dating found that users facing unlimited options report lower satisfaction with their eventual choices, not higher. The endless stream of profiles creates a perpetual sense that someone better is one swipe away.

The same pattern appears in career decisions. The maximizer doesn’t just want a good job; they want the optimal job, the one that perfectly balances compensation, meaning, growth potential, work-life integration, colleagues, location, and a dozen other factors. This perfect job almost certainly doesn’t exist, which means the search never really ends. Even after accepting a position, the maximizer continues scanning LinkedIn, measuring their choice against every alternative.

Satisficers in these domains aren’t less ambitious. They’ve simply recognized that human connection and professional fulfillment aren’t optimization problems. A good relationship with a compatible partner beats an endless search for a perfect soulmate. A meaningful job that meets your core needs beats a decade of searching for a role that doesn’t exist.

Your Invitation

This week, try an experiment. Pick one decision you’ve been overthinking, whether it’s where to eat dinner, which workout routine to try, or which book to read next. Define your three criteria in advance. Choose the first option that meets all three. Then stop.

Notice what happens in your mind. There will probably be a moment of resistance, a pull to keep looking. That’s the maximizing habit asserting itself. Sit with it. The discomfort passes faster than you expect.

The goal isn’t to stop caring about quality. It’s to recognize that your attention is a finite resource, that the energy you spend agonizing over minor decisions is energy you can’t spend on actually living. The satisficer doesn’t get a worse life. They get more of their life back.

Barry Schwartz’s research offers a gentle but radical suggestion: in a world of infinite options, the ability to say “this is good enough” isn’t a character flaw. It’s a skill. The people who master it aren’t settling. They’re choosing to be free.

Sources: