It’s January 7th. If you made New Year’s resolutions, there’s a decent chance you’ve already stumbled. Maybe you missed a workout, ate something “off plan,” or realized that waking up at 5 AM isn’t actually compatible with your life. Here’s the thing: that stumble isn’t a character flaw. It’s a design flaw in how most of us approach goal-setting.

The annual resolution ritual has a dismal track record. Research from the University of Scranton found that only 19% of people who make New Year’s resolutions stick with them for two years. Most abandon ship by mid-January. We’ve been setting goals the same way for decades, and the approach keeps failing for the same reasons: vague intentions, willpower dependency, and zero structural support.

But goal-setting itself isn’t broken. The problem is that most of us were never taught how to do it well. Behavioral scientists, psychologists, and habit researchers have spent years developing frameworks that actually account for how human motivation and behavior work. These aren’t productivity hacks or Instagram affirmations. They’re evidence-based approaches that have been tested, refined, and proven to work.

Why Traditional Resolutions Fail

The typical resolution follows a predictable pattern. You feel motivated (usually after holiday excess or a birthday reflection), declare a sweeping change (“I’m going to get fit,” “I’ll be more productive”), and rely on that initial burst of enthusiasm to carry you forward. The problem? Motivation is not a reliable fuel source.

Dr. BJ Fogg, founder of Stanford’s Behavior Design Lab, has spent decades studying why people succeed or fail at behavior change. His research reveals a fundamental mismatch between how we set goals and how behavior actually works. “People often think behavior change requires a lot of motivation,” Fogg explains. “But motivation is like the weather: it comes and goes. The key is designing behaviors that don’t rely on motivation.”

Traditional resolutions also suffer from what psychologists call the “fresh start effect.” While the new year does provide a psychological clean slate that can boost initial commitment, it also creates an all-or-nothing mentality. Miss one day? The streak is broken. Eat one cookie? The diet is over. This binary thinking transforms small setbacks into total abandonment.

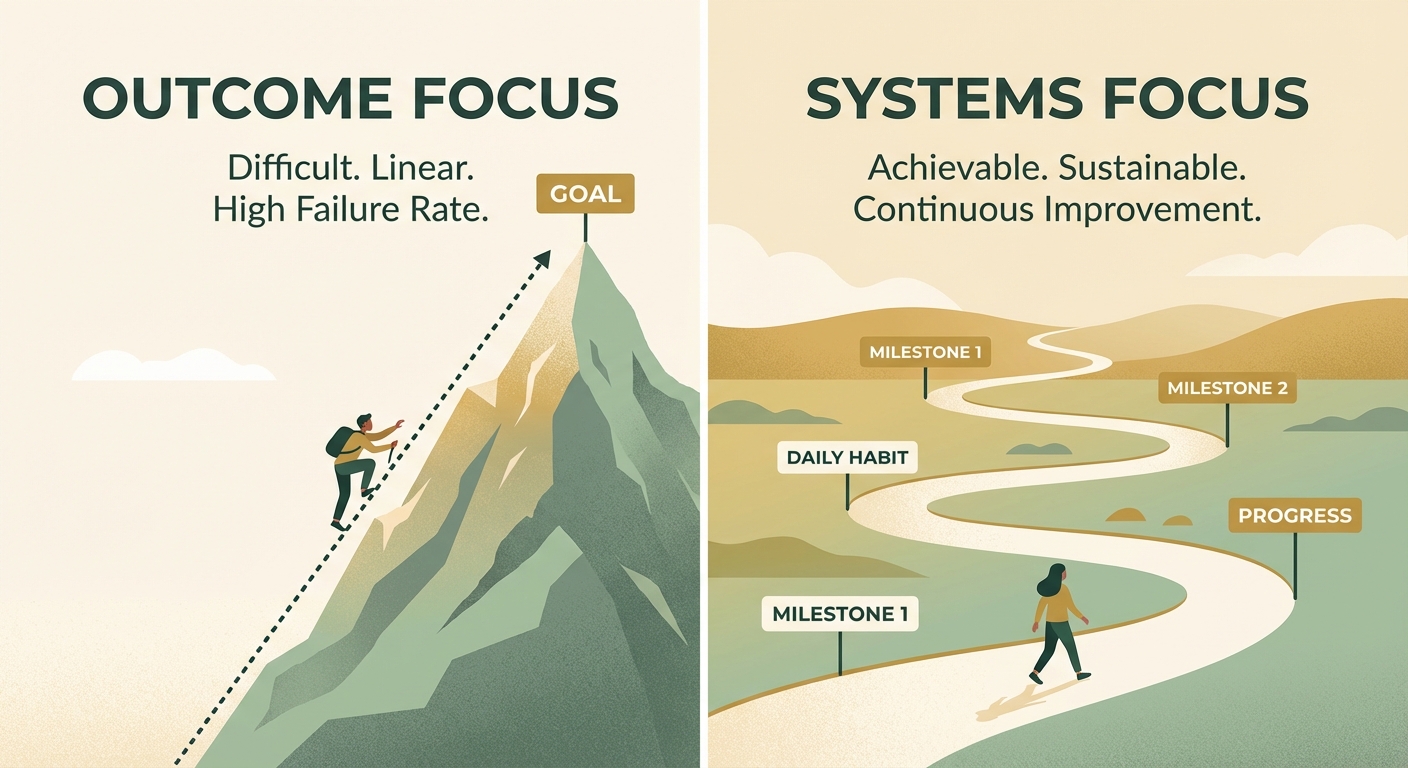

The third failure mode is what I call “outcome worship.” We set goals like “lose 20 pounds” or “make more money” without building the systems that would make those outcomes possible. James Clear, author of Atomic Habits, puts it bluntly: “You do not rise to the level of your goals. You fall to the level of your systems.”

The Identity-Based Approach

One of the most powerful shifts in goal-setting research comes from understanding the role of identity. Most goals focus on what we want to achieve. Identity-based goals focus on who we want to become. The difference is subtle but transformative.

Consider the difference between “I want to run a marathon” and “I’m becoming a runner.” The first is an outcome you’re chasing. The second is an identity you’re building. Every time you lace up your shoes, even for a short jog, you’re casting a vote for the type of person you want to be. Clear’s research shows that behavior change follows identity change, not the other way around.

This approach works because it changes the internal negotiation. When you identify as a runner, skipping a run creates cognitive dissonance. It conflicts with your self-image. But when you’re just someone trying to run a marathon, skipping feels like taking a break from an external obligation. The identity frame makes consistency feel natural rather than forced.

To apply this framework, reframe your goals as identity statements. Instead of “read more books,” try “I’m becoming someone who reads.” Instead of “save money,” try “I’m becoming someone who builds wealth.” Then focus your energy on the smallest actions that reinforce that identity. A five-minute meditation session counts as evidence that you’re a meditator. A single page read counts as evidence that you’re a reader.

The Tiny Habits Method

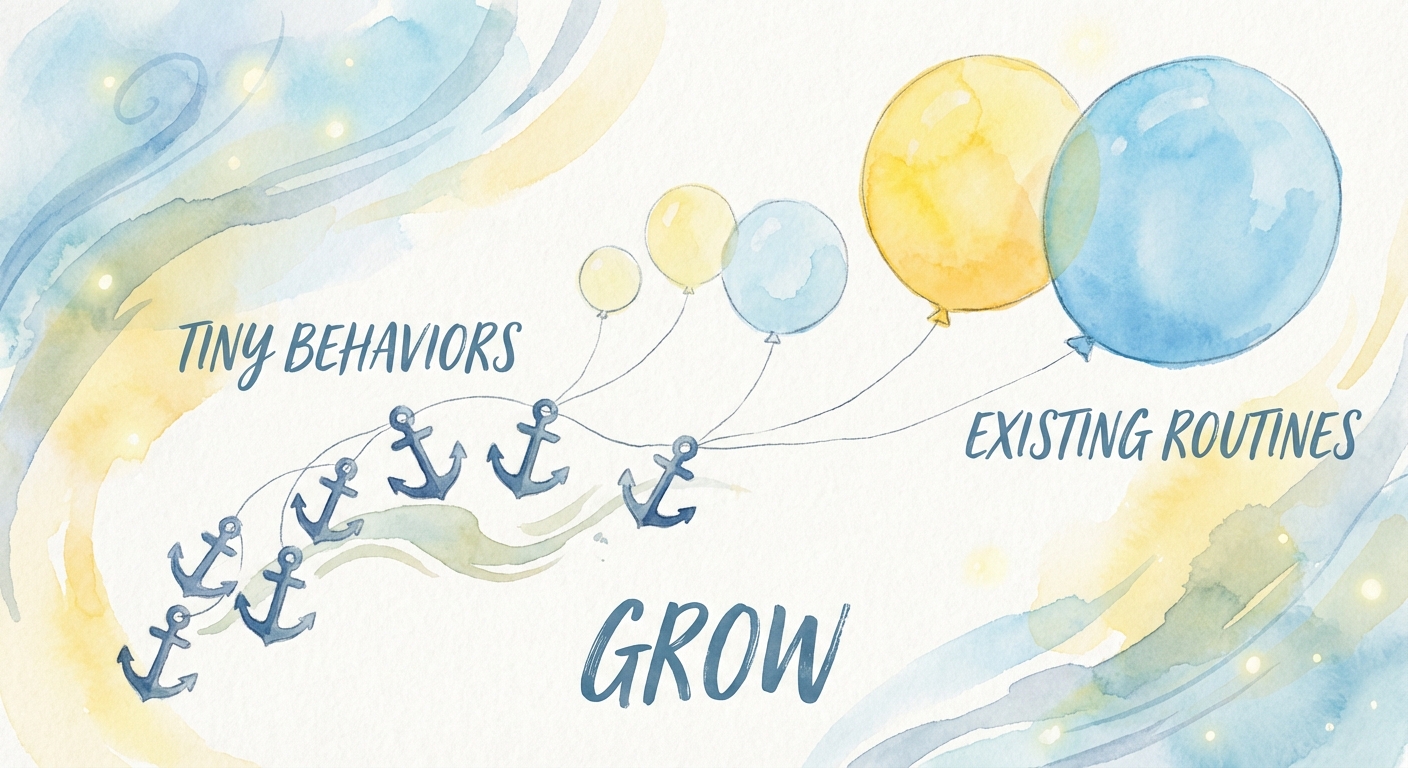

Dr. Fogg’s Tiny Habits framework addresses the motivation problem directly. Instead of relying on willpower to sustain big changes, you design behaviors so small they require almost no motivation at all.

The formula is simple: after I [existing habit], I will [tiny new behavior]. The existing habit serves as your anchor, a built-in reminder that’s already part of your routine. The tiny behavior is the seed of the habit you want to grow. Fogg’s research shows that once a behavior is established, it naturally expands. You don’t have to force yourself to do more; you’ll want to.

The critical insight is starting absurdly small. Want to floss daily? Start with one tooth. Want to do pushups? Start with one. Want to journal? Write one sentence. This feels almost insulting to your ambitions, but that’s precisely the point. The goal isn’t the behavior itself; it’s establishing the neural pathway that makes the behavior automatic.

I’ve seen this work with clients who failed at traditional goal-setting for years. One woman wanted to establish a morning yoga practice but couldn’t sustain it beyond a week. We redesigned her goal: after she turned off her alarm, she would do one sun salutation. Just one. Within a month, she was doing fifteen minutes of yoga most mornings, not because she forced herself, but because the habit had taken root and grown naturally.

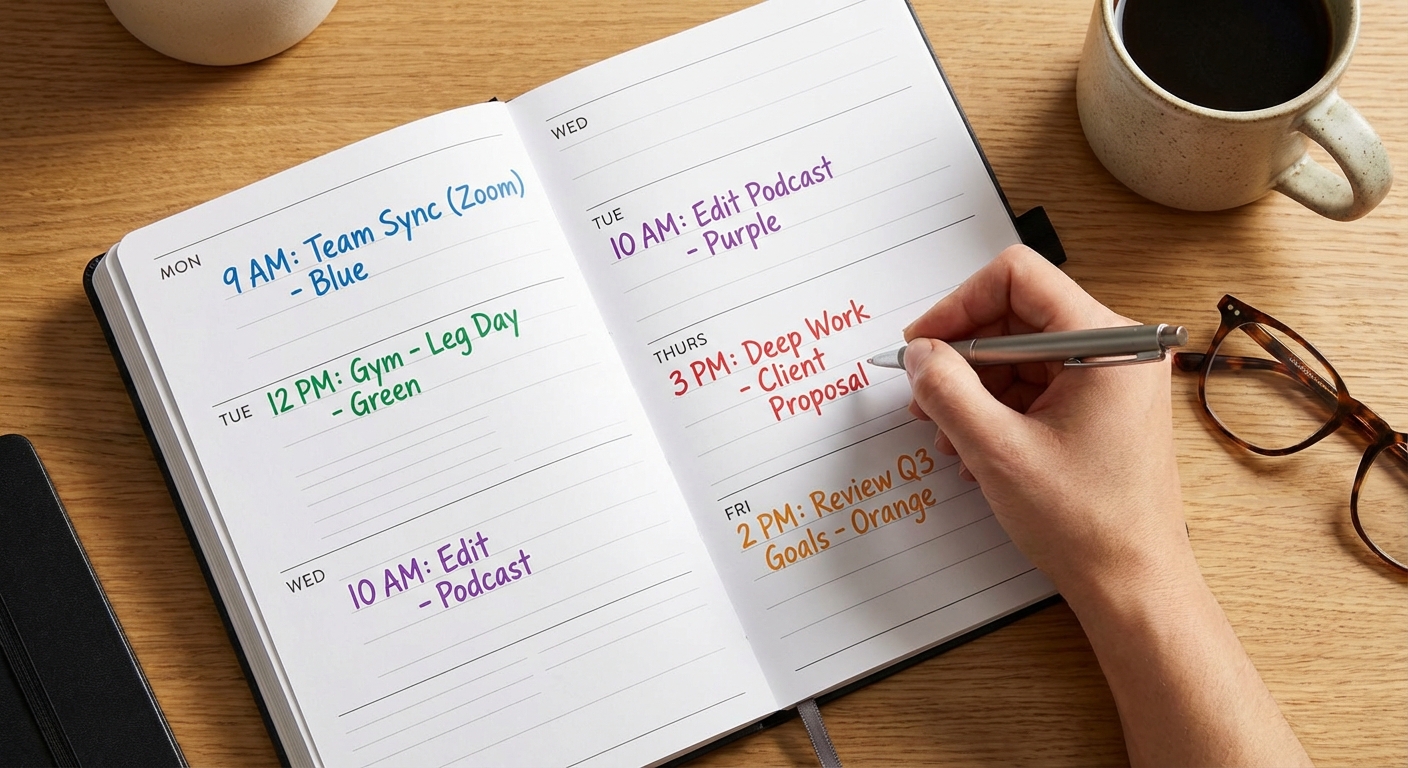

Implementation Intentions

Psychologist Peter Gollwitzer developed the concept of implementation intentions, and decades of research support its effectiveness. An implementation intention is a specific plan that links a situational cue to a goal-directed response. In plain language: you decide in advance when, where, and how you’ll take action.

The format is: “When situation X occurs, I will perform behavior Y.” Studies show that people who form implementation intentions are significantly more likely to follow through on their goals. One meta-analysis of 94 studies found that implementation intentions had a medium-to-large effect on goal attainment, outperforming simple goal statements by a considerable margin.

This works because decision-making is exhausting. Every choice depletes the mental resources you need for follow-through. Implementation intentions remove the decision. You’ve already decided what you’ll do; you just have to execute. When Friday at 6 PM arrives, you don’t deliberate about whether to go to the gym. The plan was already made.

To use this framework, take your goals and translate them into specific if-then statements. “I’ll exercise more” becomes “When I finish lunch on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, I will walk for 20 minutes.” “I’ll save money” becomes “When I receive my paycheck, I will transfer 10% to savings before doing anything else.”

Building Your Personal Framework

No single framework works perfectly for everyone. The most effective approach combines elements from multiple methods, tailored to your specific psychology and circumstances. Here’s how to build your own.

Start with a values audit. Before setting any goals, clarify what actually matters to you. Many people pursue goals that sound impressive but don’t connect to their core values. This creates motivation problems from the start. If your goals align with what you genuinely care about, the drive to pursue them feels less like discipline and more like expression.

Next, choose your identity. Based on your values, who do you want to become? Not what do you want to achieve, but who do you want to be? Write this down as a simple statement: “I am becoming someone who…”

Then design your systems. What daily or weekly behaviors would that person naturally do? Break these into the smallest possible versions, things you can do in two minutes or less. Attach them to existing anchors in your routine using the Tiny Habits formula.

Finally, create implementation intentions for any behaviors that don’t fit the anchor model. Be specific about when, where, and how. Put these in your calendar as actual appointments with yourself.

The beauty of this combined approach is that it addresses all three failure modes of traditional goal-setting. It removes motivation dependency through tiny habits. It creates structural support through implementation intentions. And it shifts from outcome worship to identity building and systems thinking.

Your Invitation

Here’s the truth about goal-setting: the perfect framework doesn’t exist, but better frameworks definitely do. The approaches outlined here have decades of research behind them and have helped millions of people create genuine change in their lives.

You don’t have to implement everything at once. In fact, you shouldn’t. Pick one goal that matters to you right now. Reframe it as an identity statement. Design the tiniest possible behavior that supports it. Attach it to an existing routine. Create a specific plan for when you’ll do it.

That’s it. No elaborate tracking systems. No expensive courses. No waiting until next Monday or next month or next year. You can start today, with something so small it feels almost silly.

The person you want to become is built through consistent small actions, not through dramatic declarations. Your resolutions didn’t fail because you lack willpower. They failed because they were designed to fail. Now you know how to design them differently.

Start small. Stay specific. Focus on the system, not the outcome. The goals that work aren’t the ones that sound impressive. They’re the ones you actually do.