You’ve set the resolution. You’ve bought the gear. You’ve told people about your commitment so you’d feel accountable. You even tracked your progress in a spreadsheet for the first two weeks. And yet, by February, you were back to your old patterns, wondering what’s wrong with you that you can’t seem to follow through on things you know are important.

Here’s the thing: you might have been approaching this backward. A major study published in Psychological Science in 2025 tracked 2,000 U.S. adults for an entire year after they set New Year’s resolutions. The findings challenge almost everything conventional wisdom tells us about goal achievement. The people who succeeded weren’t the ones who believed their goals were most important. They were the ones who actually enjoyed pursuing them.

This isn’t just a feel-good message about following your bliss. It’s rigorous behavioral science, replicated across cultures and verified with objective data. And it suggests that the way most of us think about motivation has it exactly backward.

The Research That Changes Everything

Kaitlin Woolley, a professor of marketing and management at Cornell’s Johnson Graduate School of Management, led the research along with colleagues at Yale. The year-long study examined what best predicts whether people stick with their resolutions: extrinsic motivation, where goal pursuit is a means to an end, or intrinsic motivation, where goal pursuit is an end in itself.

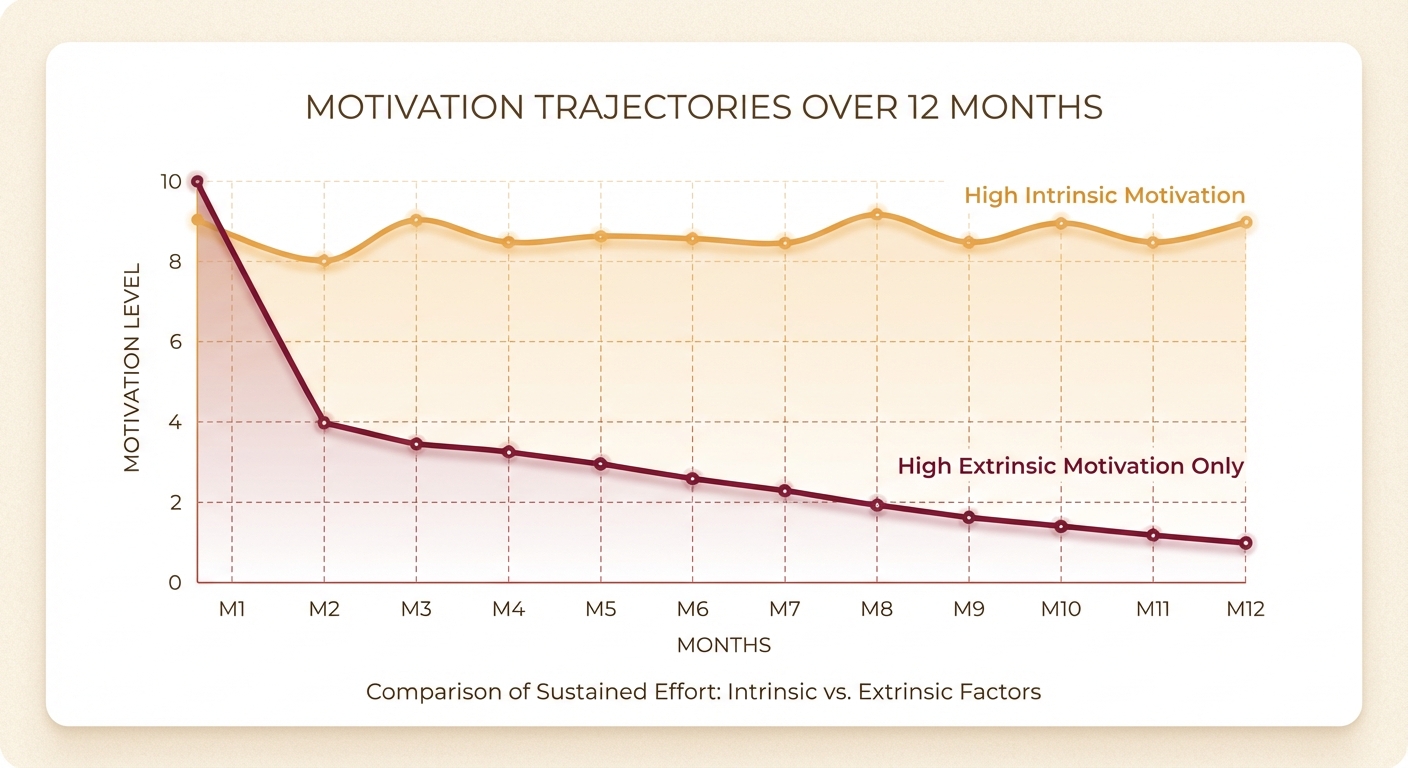

The results were unambiguous. Intrinsic motivation, the experience of finding a goal engaging, enjoyable, or interesting for its own sake, predicted adherence far better than extrinsic motivation, believing the goal was important, useful, or would lead to desired outcomes. People who set goals they thought were valuable but didn’t enjoy pursuing were significantly more likely to abandon those goals than people who genuinely liked the process.

This held true even when the goals themselves were extrinsic in nature. Participants might have set resolutions for extrinsic reasons, like losing weight to look better or exercising to prevent health problems. But among those with similar extrinsic goals, the ones who actually enjoyed the activities they chose stuck with them. Those who gritted their teeth through workouts they hated, even for outcomes they desperately wanted, gave up.

Why Fun Works: The Neuroscience

The reason enjoyment matters so much comes down to how human brains process time and reward. We respond far more strongly to immediate outcomes than to distant ones. This is well-established in behavioral economics, where it’s called temporal discounting: future rewards are “discounted” in our mental accounting, feeling less valuable than they objectively are.

When you’re pursuing a goal you find genuinely enjoyable, you experience positive feelings in the present moment. The activity itself is rewarding. You don’t need to wait months or years to collect the payoff because you’re receiving small payoffs every time you engage with the behavior. This creates a sustainable motivation loop that doesn’t depend on willpower or white-knuckling through discomfort.

Contrast this with goals that feel like a chore. When you’re grinding through an activity you don’t enjoy, your only reward is the future outcome you’re hoping to achieve. But that outcome is distant, abstract, and uncertain. Your brain has to work overtime to maintain motivation, constantly reminding you why this unpleasant activity is worth tolerating. Eventually, for most people, the distant reward loses its motivational power, and the immediate discomfort wins.

According to Woolley’s research summary, “fun is an immediate outcome. It increases intrinsic motivation, the sense that we are doing something for its own sake.” This simple insight has profound implications for how we should approach goal-setting.

Cross-Cultural Validation

One of the most compelling aspects of this research is that it holds across very different cultural contexts. The researchers replicated their study in China to test whether the findings were specific to American goal-setting values. They found the same pattern: regardless of cultural differences in how people think about goals and achievement, intrinsic motivation predicted success more consistently than extrinsic motivation.

They also tested the hypothesis with objective behavioral data, not just self-reports. In one study, researchers tracked how many steps participants actually walked over two weeks. People who said walking offered them a positive experience, who found it pleasant or enjoyable, took significantly more steps than those who said walking was important for their health but didn’t particularly like it.

“That’s a big deal,” Woolley noted, “because it shows this effect isn’t just about how people say they feel. It actually affects what they do.”

The Counter-Intuitive Intervention

In a final study, the researchers tested whether intrinsic motivation could be experimentally increased. They gave participants access to a health app and randomly assigned half of them to focus on how useful the app was while the other half focused on how fun and interesting it was to use. A day later, the “fun” group had used the app far more, scanning 25% more products than the “useful” group.

This finding suggests that the same activity can feel more or less enjoyable depending on how you frame it mentally. If you approach a goal thinking primarily about its utility, about how it will pay off later, you may actually undermine your motivation. But if you approach the same goal looking for what’s genuinely interesting or pleasurable about it, you’re more likely to follow through.

The researchers also uncovered a perverse irony: “We learned that people often predict that extrinsic motivation would be more useful in goal setting,” Woolley explained. “That belief could be holding them back though, because if a goal feels like a chore, they’re less likely to keep doing it, no matter how much they want the outcome.”

In other words, the very thing people think will help them achieve their goals, focusing on how important the outcome is, may be sabotaging their efforts.

What This Means for Your Goals

The practical application of this research isn’t to only pursue goals you naturally find fun. Some important goals require activities that don’t come with built-in enjoyment. The key insight is that when you have a goal, you should search for ways of achieving it that you also find genuinely engaging.

Want to get in better shape? Don’t just pick the exercise that burns the most calories. Pick the one you’ll actually look forward to, or at least not dread. Maybe that’s hiking instead of the treadmill, or dance classes instead of weights, or a team sport instead of solo workouts. The “most efficient” exercise doesn’t matter if you quit after three weeks. The exercise you enjoy, even if it’s theoretically less optimal, will get you further because you’ll actually do it.

This connects to what some researchers call finding the version of the goal that fits your life. The perfect approach on paper is useless if it doesn’t account for human psychology. And human psychology responds to immediate pleasure far more reliably than to abstract future benefits.

The Enjoyment Audit

If your current approach to a goal feels like grinding, consider an enjoyment audit. Ask yourself these questions:

What version of this goal would I actually look forward to? If your resolution is to read more, but you’re forcing yourself through dense nonfiction you think you “should” read, try giving yourself permission to read whatever genuinely interests you. If your goal is to be more social, but networking events feel excruciating, explore what kinds of social activities you actually find energizing.

What elements of this activity could I genuinely enjoy? Sometimes a small shift makes a big difference. Running might feel miserable until you find the right playlist, the right route, or the right running buddy. Cooking healthy meals might feel like a chore until you start treating it as creative experimentation rather than nutritional obligation.

Am I focusing too much on the outcome and not enough on the experience? This is the trap the research highlights. Constantly reminding yourself why a goal is important can actually backfire if it frames the activity as something you’re tolerating rather than engaging with. Try shifting your attention to what’s happening right now, not what you’ll gain later.

What would make this feel less like a sacrifice? The most sustainable behavior changes don’t feel like deprivation. They feel like a better version of your life. If your current approach requires constant willpower to maintain, that’s a signal to find a different approach, not a signal that you need more discipline.

The Permission to Enjoy

There’s something almost subversive about this research in a culture that often celebrates grinding, hustle, and discipline. We’ve been taught that achievement requires suffering, that if something feels easy, you’re probably not trying hard enough. The data suggests otherwise.

This doesn’t mean you should only do things that are immediately pleasurable. Some valuable experiences require moving through discomfort. And intrinsic motivation isn’t the same as instant gratification; you can find deep meaning in challenging pursuits that aren’t exactly “fun” in a simple sense. But the research does suggest that forcing yourself through activities you genuinely dislike, day after day, in pursuit of distant outcomes, is a strategy with a high failure rate.

You’re allowed to seek out versions of your goals that you’ll actually enjoy pursuing. You’re allowed to let go of approaches that feel like punishment, even if they’re supposedly more effective on paper. You’re allowed to trust that sustainable change happens through engagement, not endurance.

Your Invitation

As you think about the year ahead and whatever goals or intentions you might set, consider this reframe: the question isn’t just what you want to achieve. It’s whether you can find a path to that achievement that you’ll actually want to walk.

This isn’t about lowering your standards or only choosing easy goals. It’s about being strategic with your psychology. If intrinsic motivation predicts success better than extrinsic motivation, then designing goals you’ll intrinsically enjoy isn’t a compromise. It’s the most effective approach the research can offer.

You don’t have to earn your results through suffering. You don’t have to prove your commitment through misery. You can look for the version of your goal that lights you up, and trust that the enjoyment itself, that immediate positive experience, is fuel that will carry you further than any amount of white-knuckled determination.

The science is clear: fun isn’t the enemy of achievement. It might be the most underrated predictor of it. So give yourself permission to seek it out. Your future self, the one who’s still engaged with your goals months from now, will thank you for it.

Sources: Yale School of Management, Cornell Chronicle, Phys.org, Kaitlin Woolley (Cornell Johnson Graduate School of Management) research on intrinsic motivation published in Psychological Science.