The presents are unwrapped. The guests have gone home. The tree that seemed so magical last week now just looks like a fire hazard shedding needles on your carpet. And somewhere between cleaning up the wrapping paper and facing another day, you notice it: a heaviness you can’t quite name, a flatness where the excitement used to be.

If you’re feeling let down after the holidays, you’re not broken. You’re not ungrateful. You’re experiencing something that psychologists have studied for decades, a phenomenon as predictable as it is poorly understood. The post-holiday letdown is real, and it has nothing to do with how good your holidays actually were.

The Psychology Behind the Drop

The emotional dip after major holidays isn’t a character flaw or a sign that something went wrong. It’s a neurological and psychological response to the end of an anticipation cycle. Professor Laurie Kramer at Northeastern University describes holidays as “marker events” that reflect where we are in our lives compared to past years. They come loaded with expectations, memories, and emotional weight that no single day can fully carry.

Here’s what’s happening in your brain: during the lead-up to the holidays, you’re likely experiencing elevated dopamine levels associated with anticipation. The planning, the gift-hunting, the imagining of how things will unfold, all of this activates your brain’s reward system. Anticipation itself feels good, sometimes even better than the actual event. Research on happiness consistently shows that we often derive more pleasure from looking forward to something than from experiencing it.

When the holiday arrives and passes, that anticipatory dopamine drops. The goal has been achieved. The countdown is over. Your brain, which had been running on future-focused energy, suddenly has nothing immediate to look forward to. The contrast between that elevated state and your normal baseline feels like a crash, even when nothing has actually gone wrong.

Why ‘Good’ Holidays Can Feel Bad After

One of the most confusing aspects of the post-holiday letdown is that it can hit hardest after genuinely wonderful celebrations. You might have had the best Christmas in years, surrounded by people you love, and still feel deflated on December 26th. This isn’t ingratitude. It’s contrast.

Psychologists call this the “happiness gap,” the distance between our elevated emotional state during special occasions and our everyday emotional baseline. The bigger the gap, the more jarring the return to normal life. If your holidays were particularly magical, the contrast with regular Tuesday-morning reality is stark. Your brain notices the difference and interprets it as loss, even though nothing has been taken away.

There’s also the phenomenon of goal completion to consider. Before the holidays, you were likely engaged in goal-oriented behaviors: buying gifts, preparing meals, coordinating gatherings, decorating spaces. This purposeful activity gives structure and meaning to your days. Once the goals are achieved, you’re left with what researchers describe as an “open loop” that has closed. The motivation that propelled you forward suddenly has nowhere to go.

For some people, the holidays also bring what psychologist Susan David calls “emotional labor,” the effort of managing not just logistics but everyone’s feelings, expectations, and conflicts. By the time the celebrations end, you may be emotionally exhausted in ways that don’t become apparent until the adrenaline wears off.

Name What You’re Actually Feeling

The post-holiday experience isn’t one emotion. It’s usually a complex blend that deserves untangling. You might be feeling any combination of the following: relief that the pressure is over, grief for holidays past that can never be recreated, exhaustion from weeks of extra effort, disappointment that reality didn’t match expectation, or simply emptiness where fullness used to be.

Taking a few minutes to identify your specific emotional landscape can help. This isn’t about fixing anything yet. It’s about accuracy. Naming your emotions with precision, what psychologist Lisa Feldman Barrett calls emotional granularity, helps your brain process them more effectively. “I feel bad” keeps you stuck. “I feel the particular melancholy of a beautiful thing ending” gives you something to work with.

You might also notice that this period surfaces emotions that were suppressed during the holiday rush. The busy-ness of December often serves as a distraction from harder feelings: loneliness, grief, relationship tensions, or existential questions about the year’s direction. When the activity stops, these feelings have room to emerge. That’s not the holidays causing these emotions. That’s the quiet after the holidays revealing what was already there.

Give Yourself Permission to Transition Slowly

Our culture treats the day after a holiday as if it should be business as usual. The decorations should come down efficiently. The routines should resume immediately. The emotional hangover should be walked off like a mild inconvenience.

But transitions take time. The shift from celebration mode back to regular life is a genuine psychological adjustment, and rushing it often makes the discomfort worse. You wouldn’t expect to immediately feel normal after returning from an international trip with jet lag. Why expect instant emotional recalibration after an intense period of social, emotional, and often physical exertion?

Consider giving yourself a few days of intentional transition. This might mean keeping some decorations up a bit longer if they bring you comfort, scheduling less rather than immediately filling your calendar, or simply acknowledging that this week is a bridge between two different modes of being. Rest doesn’t require justification, and neither does moving slowly through an emotional transition.

The research on post-holiday adjustment suggests that most people’s mood normalizes within a few days to two weeks. If you’re still experiencing significant depression, anxiety, or hopelessness after two weeks, that’s worth discussing with a mental health professional. But for most people, this is a temporary state that passes on its own, especially if you don’t fight against it.

Create Small Things to Look Forward To

Since part of the post-holiday drop comes from the end of anticipation, one practical response is to create new things to anticipate. These don’t need to be major events. In fact, smaller, nearer anticipations often work better than distant big ones.

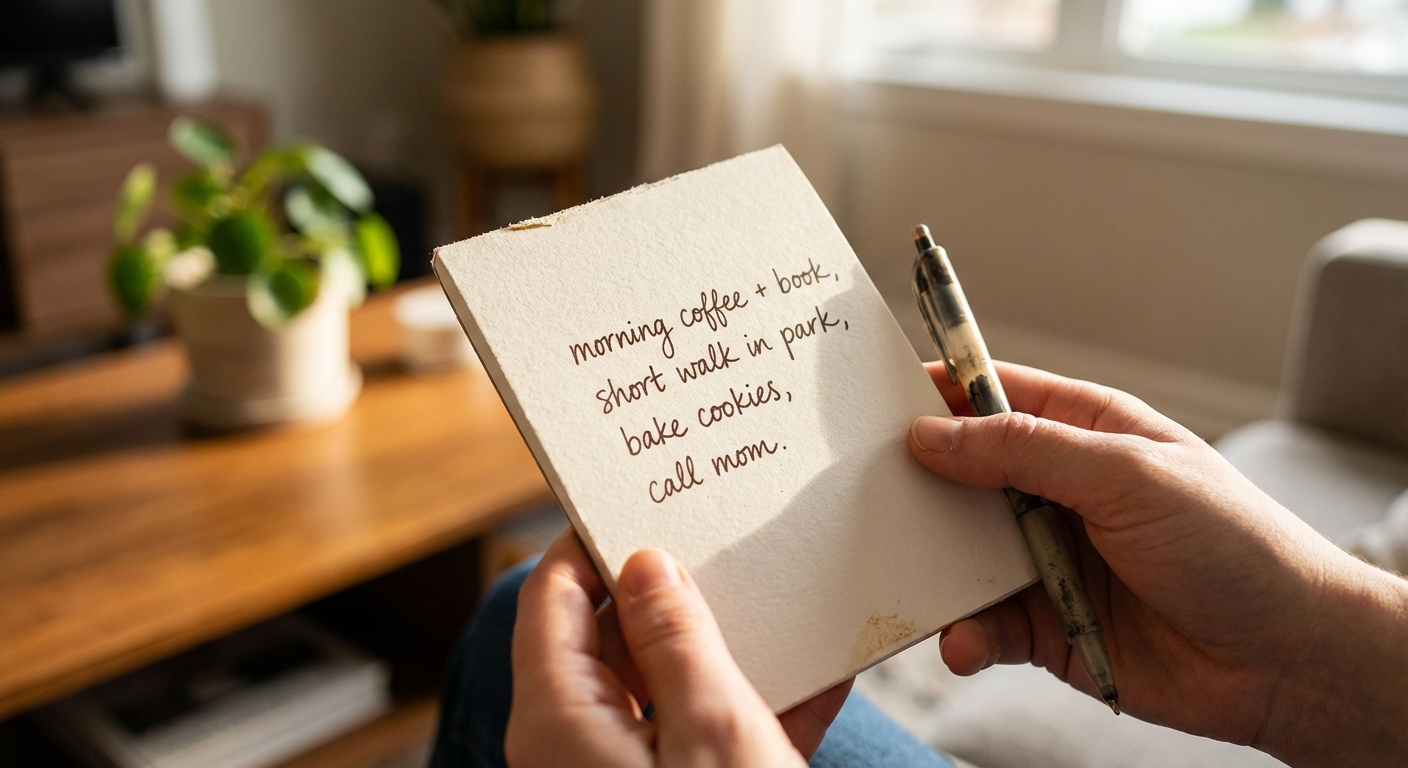

Consider what you could look forward to this week: a movie you’ve been wanting to watch, a coffee date with a friend, a walk in a new neighborhood, a book you’ve been saving, or simply an evening with nothing scheduled. The point isn’t to manufacture excitement that matches Christmas morning. It’s to give your brain’s forward-looking systems something to engage with.

You might also find value in planning something for January or February, months that often feel barren compared to the holiday season. Having even one thing on the calendar, a weekend trip, a dinner party, a class you’ve been curious about, can provide an anchor point that makes the stretch of winter feel less empty.

The Quiet Has Its Own Value

There’s one more possibility worth considering: that the post-holiday quiet isn’t a problem to solve, but a different kind of experience to have. Our culture is so oriented toward celebration, productivity, and forward momentum that we often pathologize stillness. But the space between holidays, the week when nothing much is happening, has its own particular texture.

This is a liminal time. The old year is ending, the new one hasn’t started, and you exist in the pause between. Some people find this disorienting. Others discover that the liminal space is where certain kinds of thinking and feeling become possible, the kinds that get crowded out by the noise of regular life.

If the quiet feels uncomfortable, that discomfort might be worth sitting with rather than immediately escaping. What thoughts come up when there’s nothing to do and nowhere to be? What questions have you been avoiding? What becomes audible when the holiday soundtrack finally stops?

Your Invitation

The post-holiday letdown is not a sign that something is wrong with you or that your holidays failed. It’s a predictable response to the end of an anticipation cycle, the completion of goals, and the contrast between elevated emotional states and everyday life. It’s also temporary.

In the meantime, name what you’re feeling with as much specificity as you can. Give yourself permission to transition slowly rather than forcing an immediate return to productivity. Create small things to look forward to. And consider whether the quiet might have something to offer that the celebration couldn’t.

The holidays end. That’s what makes them holidays. And what comes after, the ordinary days that don’t glitter or demand anything special from you, has its own kind of value. Even if it takes a little while to remember what that is.

Sources: Laurie Kramer’s research on marker events, Susan David’s work on emotional labor, Lisa Feldman Barrett’s research on emotional granularity.